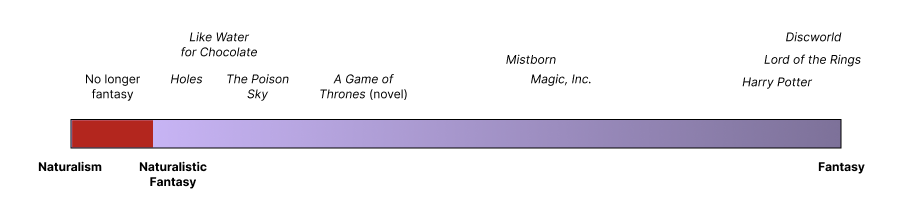

My work-in-progress novel, A Philosophy of Air, the first book in a series called The Poison Sky, fits into the fantasy sub-genre naturalistic fantasy, which, ahem, does not yet exist.

In this post, I’ll define this sub-genre, explain why I believe it fills an important gap, and suggest why a fantasy writer might benefit from considering this genre and its underlying process for their own work.

Let’s begin with some definitions. The following come from Oxford languages:

Naturalistic — derived from real life or nature, or imitating it very closely.

Fantasy – the faculty or activity of imagining things, especially things that are impossible or improbable.

These terms sound contradictory, and they are. But art thrives on contradiction, and it’s exactly this type of paradox that makes this genre strike me as ripe with potential for exploration. How do we merge what is fantastic with what is naturalistic?

This leads us to the integrated definition:

As a fantasy sub-genre, naturalistic fantasy sits at the intersection of imagination and reality, where a highly-limited set of fantasy elements intrudes into the space of an otherwise realistic world.

Naturalistic fantasy sits at the intersection of imagination and reality, where a highly-limited set of fantasy elements intrudes into the space of an otherwise realistic world.

Note that I’m using the term sub-genre a little loosely here. Naturalistic fantasy is a sub-genre in the same way that “hard science fiction” (an attachment to the rules of known science) and “soft science fiction” (an attachment instead to genre trappings such as spaceships and alien creatures) are sub-genres. Describing these as sub-genres simplifies the conversation, but it’s best to remember that these concepts exist along a spectrum. In the case of hard vs. soft science fiction, The Expanse, Foundation and The Martian are “hard” relative to “soft” science fiction like Star Wars, but the Star Trek and Alien franchises largely sit somewhere in-between, neither wholly hard nor soft.

Extend this same thinking to naturalistic fantasy, as any given work might be more or less naturalistic. It’s one end of a spectrum, on the opposite side of which sits, well, fantasy.

Hallmarks of naturalistic fantasy

So if it’s one end of a spectrum, what marks out naturalistic fantasy? Let’s begin to answer by talking about the hallmarks which define fantasy itself. Here’s a helpful definition from Wikipedia.

Fantasy is a genre of speculative fiction which involves themes of the supernatural, magic, and imaginary worlds and creatures.

What separates fantasy from other genres is its content: magic, the supernatural, strange worlds, and fantastic creatures. These trappings of the genre matter: they are why its fans gravitate to this type of story, the same way murder mysteries attract those who want to solve a puzzle, and Western fans exult in high plains and gun fights.

Of course the genre also allows for considerable crossover. Anne McCaffrey’s Dragon Riders of Pern series is essentially fantasy playing out in a science fiction setting. It turns out that science fiction fans like fantastic creatures and strange, new worlds too.

The author’s self-imposed limitations around these hallmark trappings differentiates naturalistic fantasy. Along the aforementioned spectrum, the more one embraces these trappings, the further one moves towards the fantasy end of this spectrum. One approaches naturalistic fantasy through the smallest possible door which nevertheless admits fantasy trappings.

One approaches naturalistic fantasy through the smallest possible door which nevertheless admits fantasy trappings.

Note that, like Zeno’s dichotomy paradox, one can never truly arrive at perfectly naturalistic fantasy: to do so would require the expunging of all fantastical elements, at which point we exit fantasy altogether.

Examples: fantasy

Let’s illustrate the spectrum first with some obvious examples of what sits furthest away from naturalism: full-on fantasy.

Harry Potter series

Everything you love (or hate) about fantasy appears in this series: magic spells, dragons, goblins, curses, fantastic places like Hogwarts and Diagon Alley, ghosts, wands, magic hats, fairytale creatures; they’re all represented. Lord of the Rings is roughly the same in terms of its embrace of every aspect of the genre, including creatures both from legend and invented by Tolkien himself.

These stories are about as far from naturalism as one typically gets.

Discworld series

Terry Pratchett has enormous fun in this series parodying all the tropes of the fantasy genre. We have a particularly strange world: a flat disc supported by four elephants on top of a turtle…and then an infinite number of turtles, we are told, all the way down. And populating this world are witches, wizards, vampires, heroes, adventurers, and even Death himself. It’s all done with a nod, a wink, and the odd fourth-wall break, but it’s definitely full-on fantasy (and in some ways, because of its silliness, even more full-on than the previous examples).

Examples: naturalistic fantasy

These examples are a little more difficult to detail, given that the genre doesn’t yet exist, but existing works certainly lean in this direction, some quite heavily.

A Game of Thrones, the novel

The original novel A Game of Thrones, from which the TV series was adapted, has a lot of elements that move it in the direction of naturalism: a useful, if imperfect, example because it’s so well known.

In this series debut, there’s very little fantastic about the story. Yes, the wights (essentially zombies) appear right in the prologue, but they remain a largely distant and unexplained mystery. There’s little magic other than rumors, and, at least until very near the end, no dragons other than a vaguely remembered history. Even the principle setting plays as a sort of alternate-reality Britain, complete with an admittedly larger-than-life Hadrian’s Wall, rather than as a truly strange world. Much of what appears to be magic turns out to be no more than parlor tricks, enhancing an overall sense that maybe all magic in this world is nothing but hokum.

While it’s not quite naturalism, this first novel is certainly very naturalistic. As the story develops in later novels, the fantasy elements come to fruition: dragons, magic, wights, giants, face stealers, and reanimations. It remains a harsh, unforgiving world, of course, but by the third novel or so, we’ve definitely moved well away from naturalism.

“Hard fantasy”

This sub-genre name irks me, as I’ll explain, but it’s a useful example of something which moves in the direction of naturalistic fantasy.

So-called hard fantasy comes from the same core notion as hard science fiction: just as science fiction is “hard” when it follows established scientific understanding, hard fantasy is a sub-genre that establishes hard-and-fast rules of magic, often in the form of a “different science.” But the name is problematic: hard science fiction isn’t “hard” because it’s rules-driven; it’s hard because it represents a “hard” attachment to our best understanding of available science. An analogous notion of “our best understanding of available fantasy” makes no sense at all.

Nevertheless, this can be a fun space in which to play: stories in this sub-genre tend to feature scientists trying to unravel the logic behind the magic, or wizards grappling with the implications of these rules. Here’s a fun example I remember from my childhood. It’s not exactly hard fantasy — like so many of these examples, it’s all somewhere on the spectrum — but you’ll get the picture:

Some examples of this sub-genre include Robert Heinlein’s Magic, Inc. and Brandon Sanderson’s Mistborn series.

Magic realism

Magic realism also flirts on the edges of naturalism. Stories in this sub-genre tend to exist in mostly real-world settings, usually right here on Earth, and yet somehow the rules aren’t quite what we experience in everyday life.

For example, in Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate, the main character’s cooking evokes strange outcomes which seem to amplify her own emotions. There is constant tension between the limits of what the reader accepts logically and the implication that something magical lies just below the surface.

The same type of “magicality” appears in Louis Sachar’s Holes, where the main character must atone for a sin committed by his great-great-grandfather. While everything that occurs could be explained away as random chance, it all feels just a bit too random to explain rationally. Sachar guides the reader to believe that the more “rational” explanation is some kind of deeper, supernatural agent.

So what’s wrong with these existing sub-genres?

As we’ve already seen, genres and sub-genres are slippery at best, especially today when a superhero show about a Norse god can be either science fiction or psychodrama.

As the author of A Philosophy of Air, however, the problem is that none of these describes the genre in which I’m writing. To help explain this, I’m going to have to crack open the lid on my story.

Here’s the hook:

In Nathum’s world, airships rule the skies above a sea of poison clouds, and superstition poisons the minds and hearts of men.

Ever since his mother died, Nathum has devoted himself to studying science. But when a rival power assassinates his nation’s ruler, he’s thrust into the unforgiving and deadly world of airmen, and into the politics whirling around the ruler’s brilliant, ambitious daughter.

Now this quiet scientist must learn to fly and fight, to steer a course through a world verging on chaos, before his own discoveries destroy everything he loves.

The fantastic elements are right there in the first sentence: a fantastic world with airships and a sea of poison clouds. That’s it. Sure, superstition is part of the world, just as it’s part of ours. Credulous people may believe in dragons and magic, but my hero will not meet mythical creatures and learn to ride them. Nor will he uncover a volume of lost magic and learn to master the weather. What he will do is “learn to fly and fight, to steer a course through a world verging on chaos.” The world may be fantastic, but navigating it requires the same tools that would be required in ours.

In some ways, but for its fantastic setting, this novel is closer to a Horatio Hornblower or Jack Aubrey novel than it is to Lord of the Rings. The challenges derive from coping with the difficulties of life aboard ship every bit as much as they do with confronting a hostile enemy.

So this is emphatically not “hard fantasy” as defined above. Neither is it magic realism. Both of these genres exist to justify magic in realistic worlds…a justification unwarranted in my story.

Nor can I find any other sub-genre on which to hang my fantastical cap. Fantasy has too many existing sub-genres to count, and yet none I’ve found even waves in a direction consistent with my purpose.

[As a side note, I’ll admit that I did stumble upon the term “sailpunk,” and considered this for awhile. But this fails for me in two respects. First, the term as I understand it applies to sea-going ships, not airships. It just sounds vaguely right because it puts you in mind of “steampunk,” a genre where one expects to find airships. But more crucially, the term fetishizes the ships themselves, focusing on these specific trappings rather than on the larger world.]

What do naturalistic fantasy stories actually look like?

OK, let’s get concrete with some examples.

But before I do, a couple caveats. First, let’s remember that this is a spectrum. Thus even among the made-up-on-the-spot examples I’ll cite, each one may strike you as a bit more – or a bit less – naturalistic. Second, there’s no value judgement here. A story ain’t good because it’s naturalistic. Nor is it bad. I love all the books I listed above, so no one should ever suggest that I’m dumping on traditional sub-genres. Honestly, that’d be kinda dumb.

As I pointed out above, a story approaches naturalistic fantasy when it opens the door to fantasy, but only a little. Thus it would be fair to say that naturalism may have considerable overlap with magic realism, hard fantasy, and A Game of Thrones.

Here are some example plots which might fit the bill, together with my reasoning. Observe the common thread: a single or very limited concession to fantasy, coupled with a largely harsh and unforgiving reality.

A two-bit stand-up comic with a gambling problem starts receiving text messages from a troubadour on a parallel Earth…who’s on the run from goblins. Can the two performers help each other out of their respective predicaments? Or is the whole situation nothing but an elaborate con?

So obviously this idea cracks into two aspects of fantasy: alternate worlds and strange creatures. The text message and parallel Earth elements almost make it feel a bit like science fiction. But the framing of text messaging can mean that we never see the fantasy, or even know for sure whether it’s real. This uncertainty allows the more naturalistic elements to play themselves out.

In 16th-century Florence, Galileo Galilei struggles to crack the elusive laws of magic. But an increasingly aggressive Inquisition, and his love affair with the beautiful Marina Gamba, threaten to prevent him from unlocking the most profound secret of all.

Again, genres are slippery. Obviously this could comfortably fit under the recognized category of historical fantasy. Indeed, had I been writing this story, I’d likely have simply accepted that genre designation and thought no more about this topic. But if we assume that we’re largely just substituting a hard magic system for science, and that we’re not further introducing fantastic elements, then this story also strikes me as a good example of a naturalistic fantasy tale.

Loggers destroy a tree sprite’s last refuge in the Amazon. She’ll die without a new tree, so she emigrates to America, hoping for a fresh start in a new forest. But a run-in with an immigration agent leads to a cat-and-mouse chase through Texas. Can she locate a new home before her time runs out?

This one is a modern fable. For me, it’s the sort of story where naturalism fits…naturally. I suppose this is a bit like The Shape of Water: something fantastical thrust into an otherwise modern, relatable environment. It opens the audience up to a little fantasy, but otherwise remains grounded in reality. It’s a great vehicle to discuss current, pressing issues, lightly dressed in the garb of fantasy.

Naturalistic fantasy, origin story

As a matter of full disclosure, I didn’t come up with this idea from whole cloth. As I struggled with the question of genre, I happened to re-read one of the best TV show bibles in the business, the one written by Ronald D. Moore for the 2004 reimagined Battlestar Galactica. For anyone who’s not read it, it’s an intensely well-considered introduction to the series, but more importantly, it does an excellent job redefining its own genre.

Our goal is nothing less than the reinvention of the science fiction television series. We take as a given the idea that traditional space opera, with its stocky characters, techno-double-talk, bumpy-headed aliens, thespian histrionics, and empty heroics has run its course and a new approach is required. That approach is to introduce realism into what has heretofore been an aggressively unrealistic genre.

Call it “Naturalistic Science Fiction.”

This idea, the presentation of a fantastical situation in naturalistic terms, will permeate every aspect of our series…

Moore’s “naturalistic science fiction” revolutionized what television science fiction could be, injecting his “aggressively unrealistic genre” with numerous ingredients which make it fundamentally about the here-and-now. Even though the show takes place in deep space and follows beings from another planet, everything else about it reinforces parallels to the first decade of this century, including cinema verité visuals which extend all the way to the effects, fast, dynamic editing, characters and stories ripped straight from the headlines, and a pilot episode which, while hewing closely to its 1970s subject matter, is also clearly a child of 9/11 trauma.

My re-reading illuminated that – in many ways – what Moore did with science fiction was similar to my goal with The Poison Sky. I will not be quite so ambitious as to declare my intent “nothing less than a reinvention of [fantasy]”. What I will claim is that I’ve identified something special in my story that has no exact precedent in other works I’ve read.

Call it “naturalistic fantasy”.

Does genre even matter?

It’s important to ask the bedrock question: why should anyone care? The writer in me wants to say that all that matters is a good story, well told. After all, I’m not a huge fan of westerns or war pictures, but I can name a few that stand out (High Noon, Lawrence of Arabia) as great stories, even if I’m no fan of either genre.

StudioBinder defines genre as…

A category based on similarities, either in plot, aesthetics, or the intended emotional response.

They further point out that knowing one’s genre helps set up audience expectations and to provide a roadmap for storytellers. I’d add that genre is critical for everyone in-between, from agents, publishers, producers, marketers, etc., who need to understand the intent behind the material if they hope to help give it its best shot at success.

But, as the StudioBinder video explores, setting these expectations also provides opportunities to subvert those very expectations, and in so doing, one can evolve what that genre is capable of achieving.

So? (aka, what can any of this do for you?)

In establishing and exploring naturalistic science fiction, Ron Moore was able to subvert the expectations of his genre’s audience. He delivered a new way to tell a science fiction story, without techno-babble and prosthetic aliens. He innovated his genre and kept his story fresh, innovative, and relatable to his audience.

In the realm of fantasy, audiences expect the key tropes which we discussed earlier: the supernatural and magic, along with imaginary worlds and creatures. These are fantasy’s bumpy-headed aliens and techo-double-talk. Naturalistic fantasy takes most of these tropes and subverts them to give audiences a new experience within the larger fantasy genre.

Our heroes are less apt to get magical assistance, to meet an ancient wizard who will guide them to long forgotten knowledge, to tame a unicorn or slay a dragon. They won’t slip between the sheets of a magical lover or between the thin fog separating realities. They’ll have to solve their problems much like the rest of us mere mortals.

Or maybe they can and do do these things. It’s a spectrum, and where your tale lands on that spectrum may be different than where mine does.

The point is the surprise, the variety, the ability to play with and subvert the available options and our audience’s expectations.

We, too, can rethink what our genre can deliver.

What do you think? Are you familiar with existing stories that fit into the naturalistic fantasy genre? Or perhaps there’s a better way to describe it. Tell me about it in the comments.

A Philosophy of Air is my work-in-progress novel. It’s the first volume in the series The Poison Sky.

My blog deals with a variety of topics which interest me, including etymology, language, writing, and the city of San Francisco. Please consider subscribing.

Leave a Reply