Oddly, I’d never before read any Jules Verne.

I’ve now read three of his books in quick succession as research for my own novel.

[Spoiler alert if you’ve never read any of the following.]

Jules Verne has a reputation as a giant of early science fiction. He’s lauded as a visionary, a storyteller, and an influencer whose tales have been reimagined time and again. He understood and related much that was of current scientific interest and predicted a great deal of what was to come. Many say that he predicted the future.

So when I set to reading a few of his novels – having sadly neglected this literary giant for so much of my life – I was prepared for the most delightful of excursions. Dated, certainly, but magnificent nonetheless.

What I got instead was shocking: racism, sexism, and an almost complete lack of actual storytelling.

Jules Verne: Racism the conqueror

Let’s begin with the extraordinary racism.

What we see in two of these novels – Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea and Around the World in 80 Days – is what I’m going to somewhat apologetically excuse as “ordinary” 19th century racism. It’s the type of “neglectful” racism one might accept as nothing worse than European demagoguery. From that perspective, people from the rest of the world are just not as civilized, intelligent, resourceful, etc. as Europeans. It’s not good…but if one reads 19th century European literature it pretty much comes with the territory.

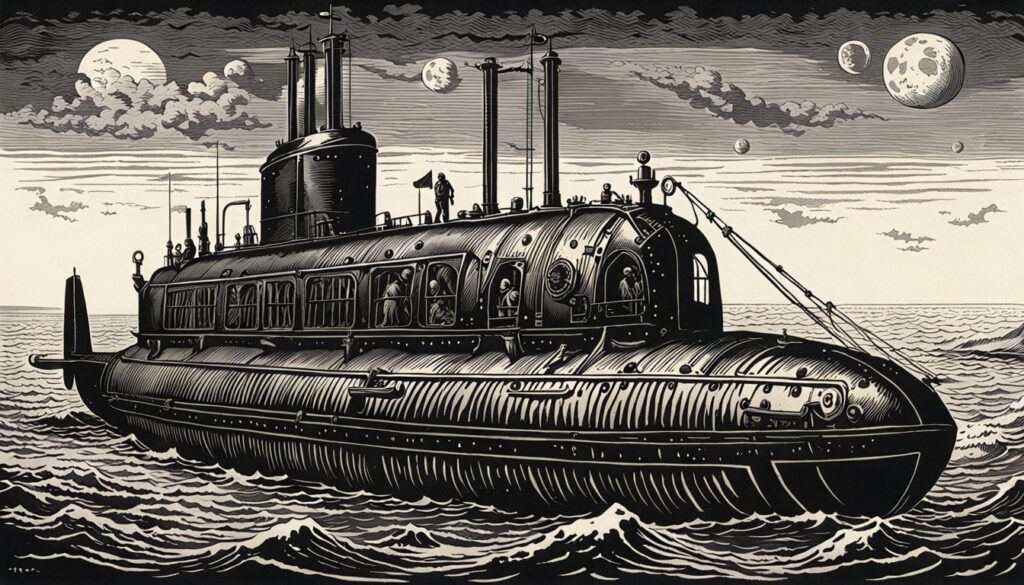

Now, in Twenty Thousand Leagues the characters don’t interact with many people. They are largely confined to Captain Nemo’s submarine. So this is less of an issue. And you could just about defend Phileas Fogg, the hero of Around the World, given that he marries Aouda, an Indian girl, at the end. But let’s not miss the fact that Verne describes the girl thusly:

“She had received a thoroughly English education in that city, and, from her manners and intelligence, would be thought a European.”

(French: Elle avait reçu dans cette ville une éducation absolument anglaise, et à ses manières, à son instruction, on l’eût crue Européenne.)

He also describes her as – ahem – “as fair as a European”. (French: Cette femme était jeune, blanche comme une Européenne.) Note that the French reads blanche, i.e., “white”.

In Robur the Conqueror, however, Verne’s racism shifts from neglectfully “of his times” to actively disgusting. He describes his lone black character in the most appalling terms. This includes various racially charged stereotypes.

Frycollin, servant to one of the main characters is described as

“an egregious coward”

(était un parfait poltron)

He has

“the head of a fool and the carcass of an imbecile”

(une tête bêtasse sur un corps de gringalet)

He is

“Grinning and greedy and idle, and a magnificent poltroon”

(Grimacier, gourmand, paresseux et surtout d’une poltronnerie superbe).

Everything within the narrative suggests that Verne fully embraced these views as racial characteristics. Frycollin doesn’t grow or change and serves as nothing but what I believe is intended as the broadest and most abhorrent comic relief.

In this context, the title character’s use of the n-word is perhaps unsurprising if no less shocking.

(On this latter point, I’ll grant that I’m reading an English translation and only referencing the original French. As I read the native version (and I’m not a native French speaker) the word used may in fact be more akin to “negro”. Had the rest of the volume not so thoroughly convinced me of where Verne stood, I might have accepted it as nothing but a poor translation.)

Jules Verne: Around sexism in three novels

One must also point to the near absence of female characters. Even in Around the World, Fogg’s “love interest” is barely a character: she’s a beautiful, nearly silent damsel in distress whom Fogg bravely rescues. After that, she’s mostly just there until she becomes a convenient means to a happy ending in the final chapter.

In the other two books, women only appear at the furthest end of a telescope. One wonders whether Verne had ever encountered such creatures in real life.

If in any of his novels Verne ever gives a woman the opportunity to string together more than a couple sentences, I can only imagine that they would be calculated to confirm the notion that women are best admired, not heard from. Given my overall reaction to these three books, I doubt seriously that I will trouble myself to find out.

Jules Verne: Not a league of story under (or over) the sea

Finally, looking at these books as narratives, it seems Verne didn’t go in much for actual storytelling. All three novels tell essentially the same tale: an emotionally detached genius with disdain for his fellow man executes an extraordinary circumnavigation of the globe.

But what follows next? Not much, as it happens.

In all three cases, the “story” is much more a travelogue, a cataloguing of sights and locales, an explication of the means by which the journey is achieved, rather than any growth of character or development of story. Relatively few actual events happen.

From atop their airship, the captive heroes of Robur watch territories sweep below them. From within their submarine, the captive heroes of Twenty Thousand Leagues observe the aquatic flora and fauna float by. In Around the World Phileas Fogg – perhaps a captive of his own ennui and detachment – passes through many spectacular corners of the world by boat, train, and sled. But the notion that a person can actually be changed by these experiences, that a story is more than a travelogue, seems utterly lost on Verne.

I will concede that in Around the World the hero experiences a modicum of growth – he works out that maybe having a wife wouldn’t be so bad – though it is really his companions and the reader who grow to appreciate him, rather than the other way around.

Were one to write these tales today, one would immediately approach them – at first blush at least – as Golden Fleece narratives: the hero embarks on an extraordinary journey. There are adventures to be had and marvels to be seen. But the most important thing they find along the way is themselves. They grow.

Doesn’t happen here.

Thoroughly modern Verne

It’s notable that in the 2021 Around the World in 80 Days miniseries starring David Tennant and Ibrahim Koma, they cast Passepartout as a black man and Fix as a woman (Leonie Benesch). And the storytellers take great care in their marketing videos to express that they have expanded Fogg’s journey to include an actual character arc.

This is not something you normally need to point out. Today we assume character growth. It’s a pretty fundamental aspect of any story. And of course these creators convert the story into a classic Golden Fleece narrative.

Mind you, the lead continues to be – ahem – a white man (but yeah, I do like David Tennant).

Twenty Thousand Leagues has been dramatized many times, but it’s notable that there has only been a single film adaptation of Robur…thankfully precious few have felt the need to return to that poisoned well.

So…Jules…we need to talk

In sum, Jules Verne’s notion of the novel seems to begin and end with the premise. There’s something of interest in his obviously deep understanding and interest in the science of his day. But this is not great storytelling. And the problematic chauvinism makes for uncomfortable reading, even excusing the century and a half separating us.

Verne’s novels leave me profoundly disappointed in the book and in the man himself. I had hoped to enjoy this reading, but can view these now only as moderately useful research, not as novels with great literary value.