What fantasy maps actually do

As follow-up to a prior post, I want to talk again about maps. This time not what I’ve drawn but rather why I drew it.

In other words, what’s the point of a map in a fantasy novel?

Why maps?

We’re all familiar with fantasy maps from books we read as children (and some of us continue to read these as adults). While there’s no rule, it’s interesting to note that no other genre leans quite so heavily on the trope of the world map.

Certainly some science fiction books do this, and some history books as well. But if a story takes place in Alabama or France, there’s a pretty good chance — the American educational system notwithstanding — that we have a reasonable understanding of the location. And unless the story really requires a deep knowledge of a location, particularly in the context of a journey, history, or military campaign, books rarely include a map.

Fantasy is different

By its nature, a fantasy story (and sometimes science fiction) often drops us into a completely alien location. In addition to the usual cognitive load of characters, relationships, and plot, fantasy frequently saddles us with magic systems, fantastic creatures, improbable social or physical rules, customs, and languages. On top of all this, the author piles on place names that — at least to begin with — mean little.

The Shire, Fangorn, Minas Tirith, Barad-dûr.

Havnor, The Hands, Hur-at-Hur, Selidor.

Braavos, Valyria, Dragonstone, Winterfell.

Hogwarts, Diagon Alley, Godric’s Hollow, Ottery St Catchpole.

Notably, only the last of these (in the books) lacks a map. Presumably this is because the Harry Potter books actually give you real-world anchors for most locations. (The stories take place in Britain, with Hogwarts somewhere “north,” perhaps in Scotland; Diagon Alley is in London; Godric’s Hollow is stated to be in the West Country; and Ottery St Catchpole’s in Devon.)

Maps allow the fantasy author to offload at least a certain amount of cognitive load. If I can’t remember anything else, at least when the author tells me that we’re in Nünøirînén, I can locate it on the bloody map.

Does Mîsøë-Áìngörüümånør even have a south?”

Another key value for the reader: she gets an up-front feel for the world even before beginning to read. Rather like cover art, the map’s design reveals something of what to expect within. Is the map packed with forests and mountains? Cities? Scattered continents or one big land mass?

Example: Lord of the Rings

Let’s look at one of the most famous fantasy maps ever created: Middle Earth from Lord of the Rings.

In this map we see a rich and mostly wild world: forests, mountains, rivers, and woods. The place names sound exotic and yet — at least to an English reader — vaguely familiar, as if this world has historical resonances rhyming with our own. The focus is on the land, not the sea, and on the many, many challenges our adventurers will face.

Besides all this, there’s information in the graphical detail: rune edging, calligraphy, staining. Certain terms make sense to ground us — “forest” “shire” river” “hills” — while others mean little at first glance. This map is designed to draw the reader in, to feel as if we’ve unearthed something ancient, full of the promise of peril and discovery.

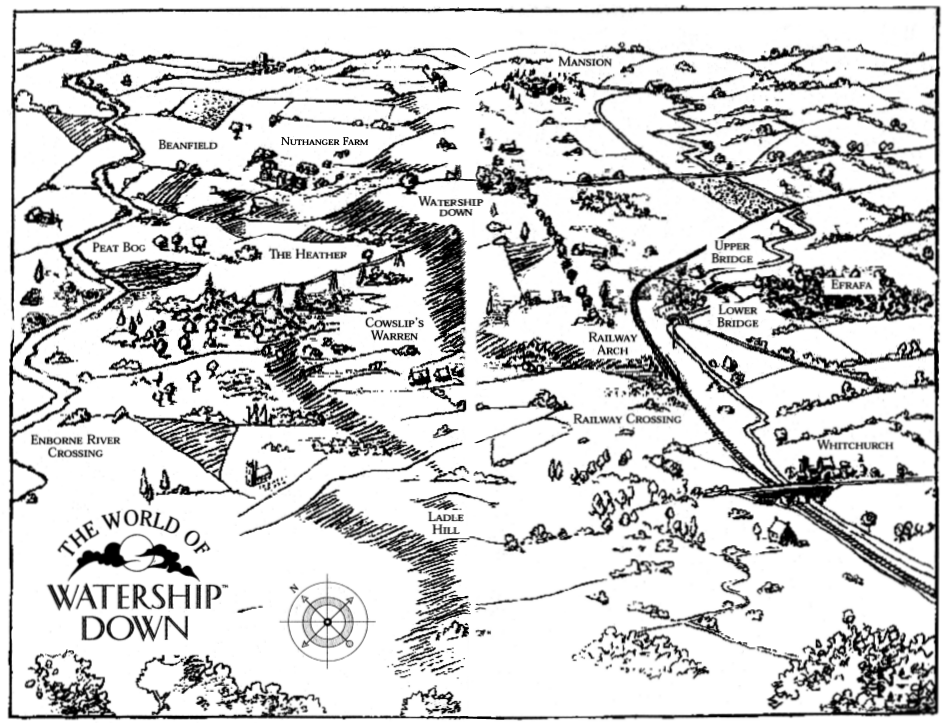

Example: Watership Down

Now compare the map of Middle Earth to the world of Watership Down.

Watership Down tells the story of a group of rabbits trying to establish a new home. (In fact it’s a retelling of The Odyssey if you squint.) In this map, we immediately see a much smaller domain integrated with recognizable real-world objects: a peat bog, hills, railway arch, farms. We can intuit that this entire “world” covers only a few square miles, and as soon as we comprehend that the story is about rabbits, we understand the reason why.

Photo by David Buttery.

Again, the style of the map suggests what to expect: the simple, serifed font, the rough drawing style, the simplicity of the compass. All of this feels more like something adapted from a naturalist’s sketchbook rather than some ancient document.

Value for the author

The value of the fantasy map doesn’t end with the reader. It’s useful for the author as well.

As I pointed out in my post about an airship’s layout, there’s considerable value for the author in clearly understanding the physical space in which the story takes place. How long does a journey between two points take? What are the possible or necessary obstacles? What seasonal events may alter those conditions?

All of this allows the author to enrich a world and raise useful questions.

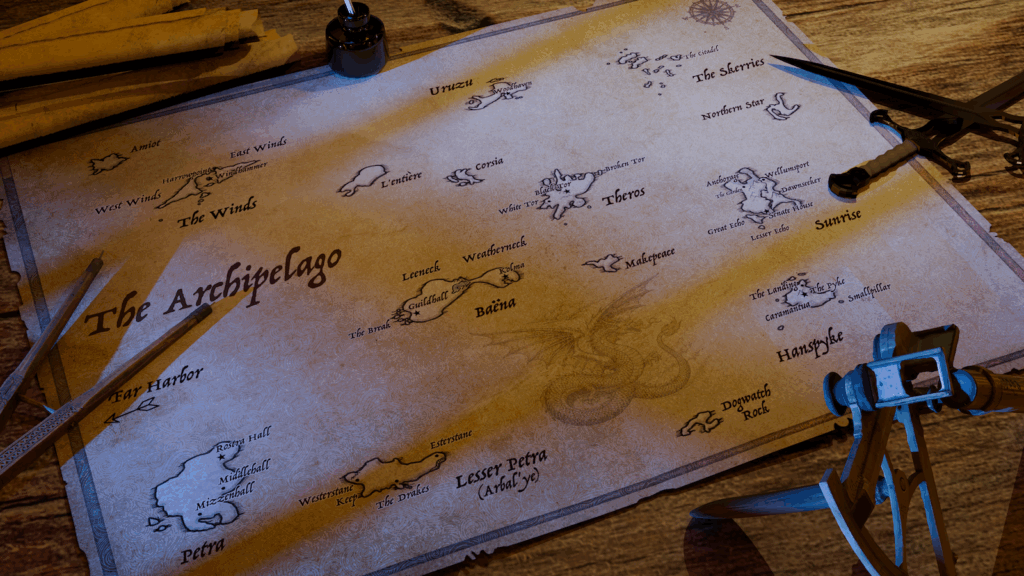

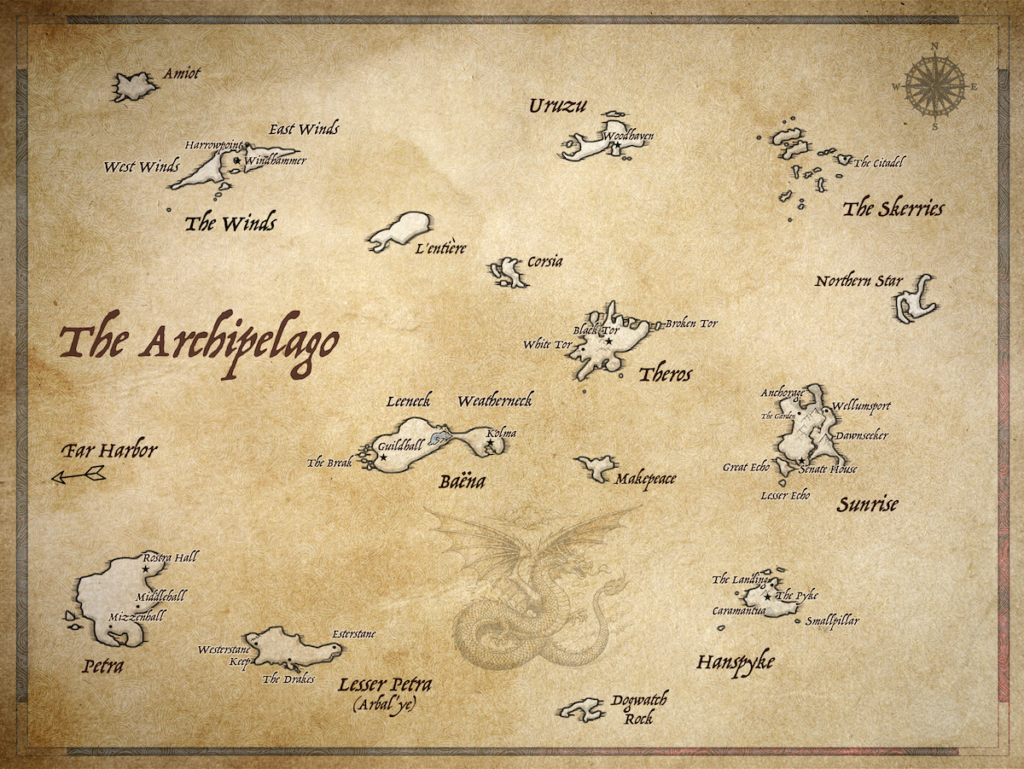

Allow me to return to my own map.

Example: A Philosophy of Air

Allow me to start by saying that this map is my own work. And I’m not an artist. I’ve attempted to create something fun to share, but let’s not confuse my scribblings for professional work. With that said…

What does this map communicate to you? (Actually, very seriously, I’d love your comments on this.)

What I’ve attempted to convey in terms of the world itself is a remotely scattered archipelago, perhaps a little like Ursula LeGuin’s Earthsea, but decidedly less densely packed. The people of my world are remote from one another, physically, emotionally, and politically. Some nations sound (to the English-speaking ear, at least) somewhat familiar. Others sound more alien.

I picked some names, such as Woodhaven, The Landing, Wellumsport, and Guildhall, to evoke important aspects of the world. Woodhaven is the capital of an island with great forests. Wellumsport refers to an important historical figure. That sort of thing.

Other place names were picked simply for the sound or idea they evoke.

The map helps me think

What’s important, however, is that as I name the thing (and yes, the names change constantly during development) I’m drawn to ask questions. Why that name? Has it always had that name or has it changed over time? If so, what brought about the change? What’s special about this place? What kind of resources does it have? What kind of government? Do its inhabitants worship a particular religion or speak a particular language? Who are they historically connected to? As I answer these questions, I enrich my world and provide lots of material which can later feed into my story.

There’s also an arrow pointing to a place called Far Harbor, suggesting that there’s more to the world than we see. So what’s that about? [Psyche! Totally not answering that.]

In terms of art and feeling, I’m hopefully evoking the sense of an old ship’s chart, which prepares the reader for the idea that this is a sailing adventure. The dragon motif — something you sometimes see on period maps — is there to remind us that sea depths (in my world’s case, a sea of acidic clouds) evoke superstition and fear of disaster.

Stepping back one more level

If you’re worldbuilding, I’d urge you to look at your map even more abstractly.

What’s your story really about? What’s its theme?

As the old saying goes, a picture’s worth a thousand words, so what does this map — this picture presented right at the front of your book — convey to your audience about your underlying message? Are you talking about cruelty? Love? Duty? Fellowship? Sorrow?

Whatever your theme, when you understand your story at a deep level, you’ll see that a good map can be a vehicle towards communicating not merely a physical journey, but an emotional and thematic one as well.

My blog covers various subjects, including writing, tour guiding, and my work-in-progress fantasy novel A Philosophy of Air.

If you find what any of this interesting, please take a moment to share it with others and subscribe. You can also follow me on Substack.

Leave a Reply