A deck-by-deck tour

Hey folks! If you’re new, welcome to my blog. I’m currently digging deeply into the worldbuilding elements of my work-in-progress fantasy novel, A Philosophy of Air.

A mea culpa

It’s occurred to me that my recent worldbuilding posts have perhaps been poorly conceived, simply explaining what I’ve created, instead of focusing on why. The latter is probably the more interesting question.

In today’s post I introduce you to the deck plan of an airship. Before getting into the details, I’ll explain why this was a useful exercise.

An aside: what these posts aren’t about

My last post included this point, but I feel it bears repeating with added emphasis. My novel isn’t about airships…that’s just setting. Airships are a fun, creative fantasy environment, and a metaphor for the themes which my story explores.

My novel — like any good story — is about characters struggling against difficult internal and external challenges. About people coping with big ideas and how those ideas impact the world around them.

What these posts are about

Fun!

I’ve put years of creative effort into fashioning a richly-textured world, one I hope readers will find intriguing.

But these posts are about something else: the little challenges and intricacies that went into creating that world. That’s a story unto itself, and one I hope you’ll find at least entertaining and possibly even useful.

If you’re thinking about constructing a world, perhaps for a novel, screenplay, or game, you might enjoy seeing how I did it. Or maybe you’ve created a world yourself and you’d like to share and compare notes.

If you just think that airship battles sound cool, get lost!!!

Joking, of course. You’re welcome here, too!

Welcome aboard the stormchaser Harald Jorem

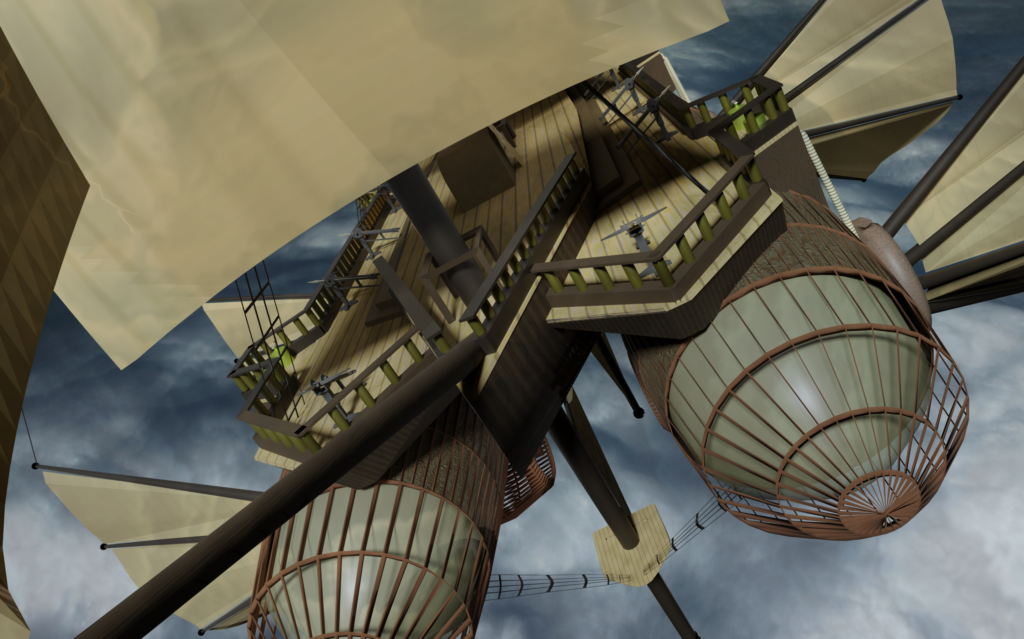

In today’s post, I’m going to walk you through another map.

You might recall me doing this once before, introducing the islands of the Archipelago. Today’s map represents a smaller scope: simply the deck plan of one of my airships. A large percentage of my story takes place aboard a specific ship and in that respect, the “world” of my story is as much this specific ship as it is the Archipelago in general.

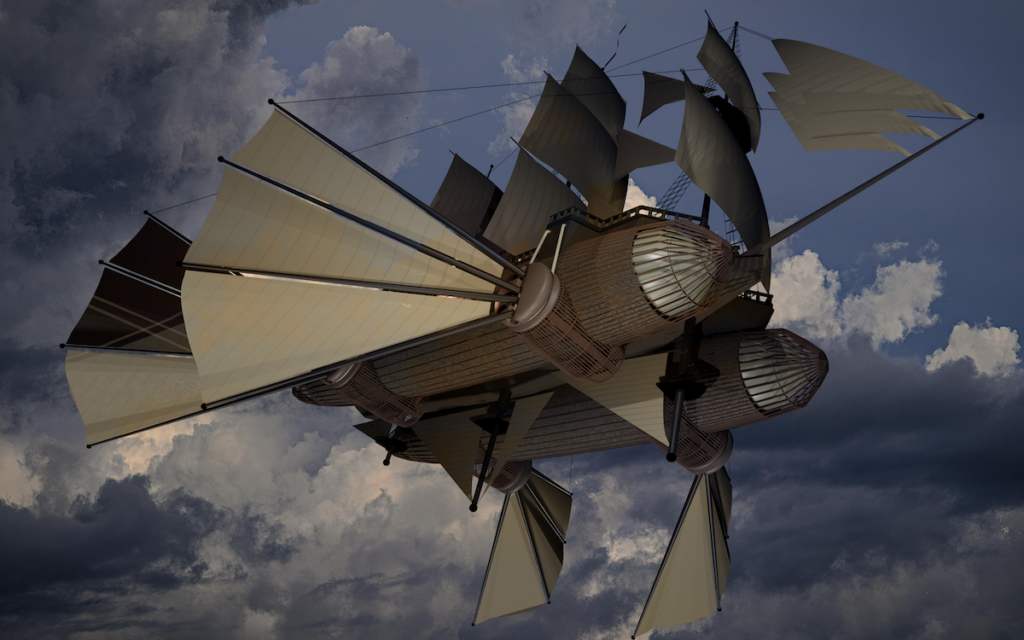

Harald Jorem is a three-masted stormchaser — a fighting ship — within its world roughly equivalent to a second-rate of the Napoleonic era. In this post, I’m offering a deck-by-deck tour, showing you around, kicking the tires. (Yes…no, there are no tires.)

The virtues of creating such a visualization

So why create a map like this? It’s clearly not something I plan to share with my reader.

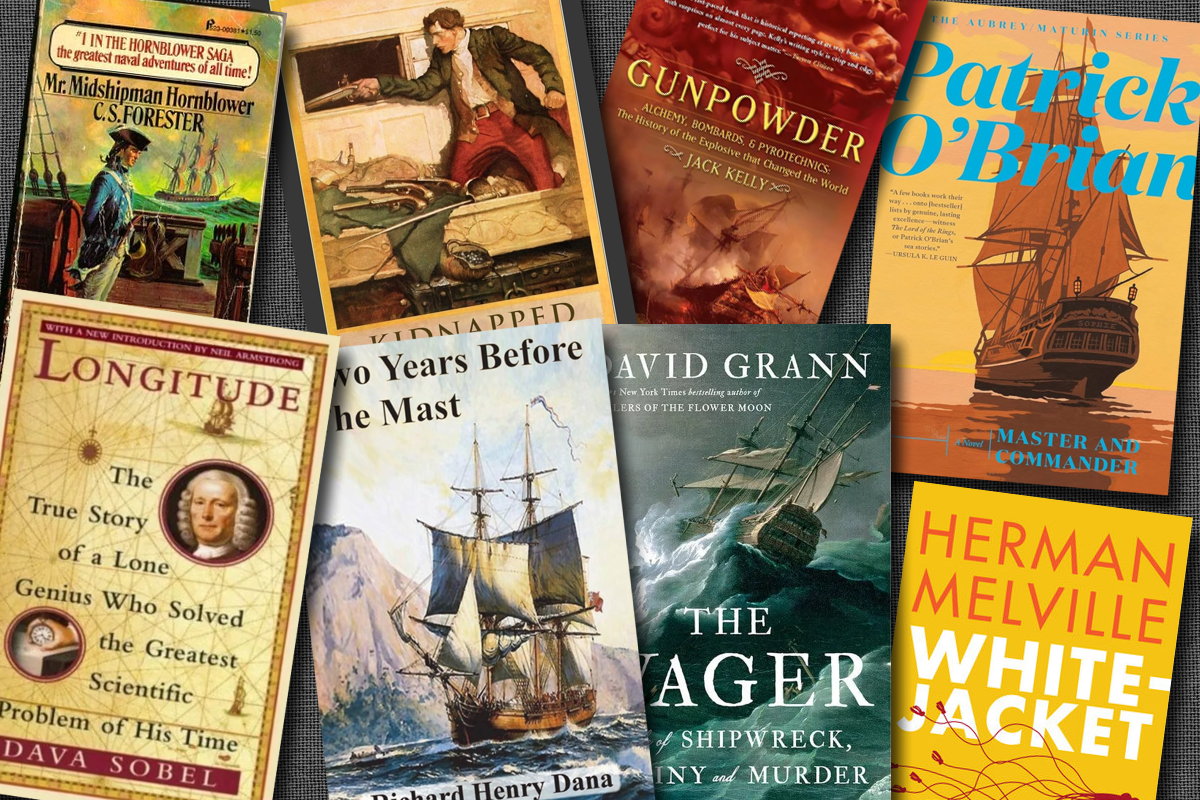

Well, a lot of my research comes from reading first- or secondhand source material, such as the works of Patrick O’Brien, Richard Henry Dana, Dava Sobel, or David Grann.

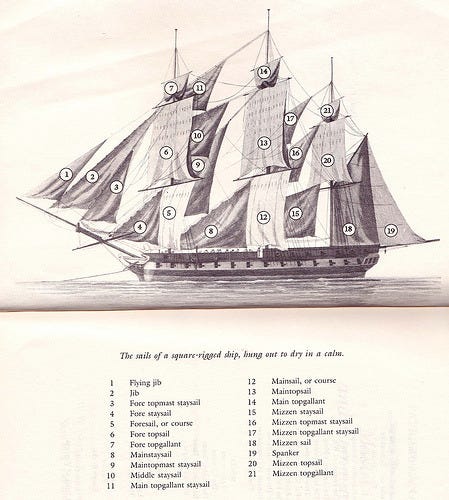

I’ve also assembled a large quantity of historical images (you’ll find one of these a bit further down the page) which I find incredibly helpful reference material when trying to differentiate the million-and-one details of a sailing ship.

But a (perhaps not-so) surprising amount also comes from my own head. Those authors and images certainly inform my story, but fantasy is all about flights of fancy (in my case you can take that quite literally), so I spend a lot of time dreaming up utter rubbish which I hope to convert into something interesting.

This deck plan helps me keep my world organized, consistent, and believable to my reader. It helps me think through the concrete details of my characters’ lives. Sometimes it even helps me create specific episodes. For example, knowing the exact relationship between a specific fighting position and the surgery helped me choreograph a particular scene (which I shan’t discuss here in detail).

Another mea culpa!

I suppose I should point out that these deck plans aren’t intended to be art pieces. They simple, functional maps serve my private use as a writer. I’ve spent exactly zero seconds gussying them up for public consumption.

I’m sharing them as artefacts of my worldbuilding journey, so I’ll ask you to forgive me if they make your skin crawl a little.

If they make your skin crawl a lot, it’s possible that the art pieces themselves are not the problem.

Everything above the deck

Like sailing vessels in the Age of Sail, airships in A Philosophy of Air have a complex array of sails. In fact, these sails are more complex than their historical counterparts, a point I detailed in another post.

Without repeating everything I wrote there, let’s just stipulate that (more-or-less) everything you’d expect to see in a circa-1800 frigate appears above deck on one of my airships.

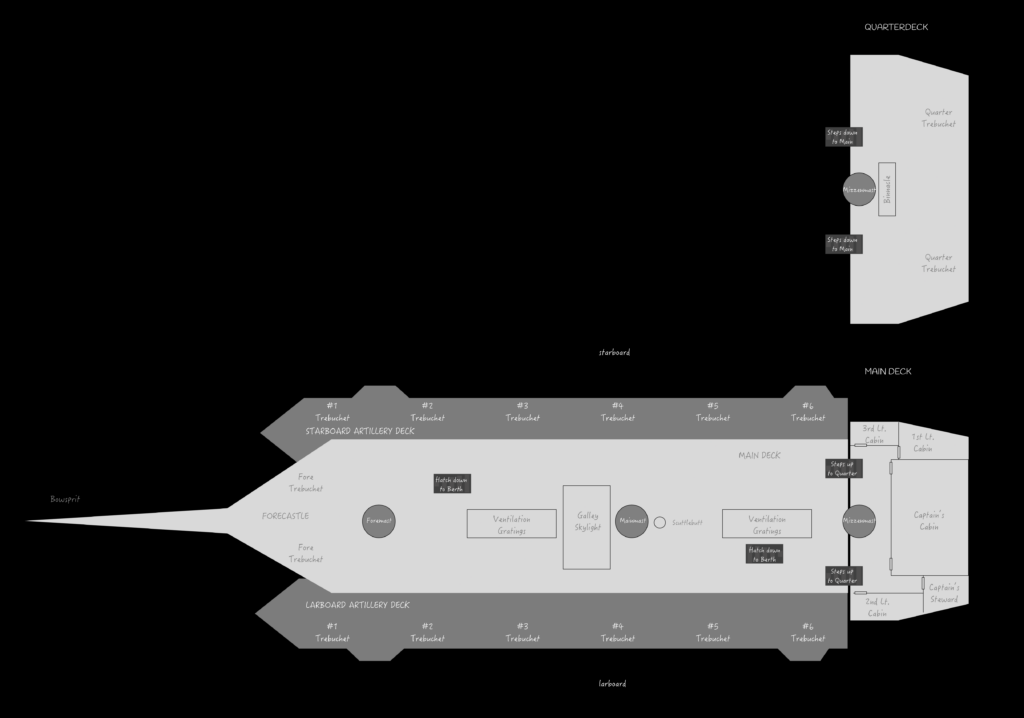

Main deck, quarterdeck, artillery decks, forecastle

And in fact, the main deck, quarterdeck, and forecastle are rather similar.

The raised quarterdeck affords a view over the remaining decks. Not an unusual Age of Sail setup.

But here we come also to the first big difference: artillery decks.

My airships are not blimps overhanging small gondolas: the surprising lifting power of sursic gas allows far larger weights to be carried, so for reasons of stability and visibility, airships are typically arranged more like catamarans, with honeycomb-like sacks to starboard and larboard of the main hull. Given their importance to everyone aboard, it should come as no surprise that these sacks are the most heavily-armored components of the ship.

The decks on either side sit above these sacks, and furnish a platform for artillery, which on an these decks consists largely of trebuchets, a sophisticated style of catapult. This world has no conception of gunpowder, so we’re not trading cannon fire, though as you might imagine, it doesn’t take a cannonball to deal heavy damage to a lighter-than-air ship. But as we dig into the bowels of the ship, you’ll see that this isn’t a ship’s only armament.

Abaft the main deck we see, under the quarterdeck, the sleeping quarters for the ship’s lieutenants, the captain’s steward, and, the great cabin where the captain himself works, dines, entertains when he so chooses, and lays his head.

Berth deck

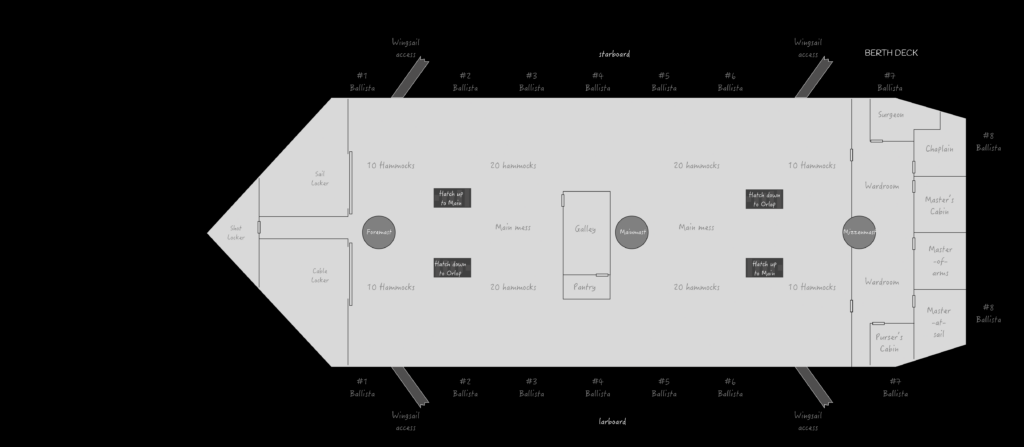

Below the main deck, we come to the busiest deck aboard Harald Jorem, the berth deck, so-called because it’s where the majority of the enlisted airmen sleep.

But airships, much like sailing ships of old, rarely use any space for but a single purpose. In the days of Nelson and Villeneuve, even the captain’s cabin would be converted into a fighting space. So it is here on the berth deck. The men sleep in hammocks, stowed when not in use. The men lower hanging tables for dining.

There’s also, naturally, a lot of room for fighting machines, which on this deck means ballistas, which are essentially huge, mounted crossbows. Crews disassemble these weapons when not in use and reassemble them as required.

Other features of the berth deck include a shot locker for ordnance, sail and cable lockers, and an aft space containing the wardroom, where the majority of ship’s officers dine. Note that in battle the men break down the wardroom’s walls. Finally, certain quarters serve specific members of the crew, such as the surgeon, chaplain, and master.

Orlop deck

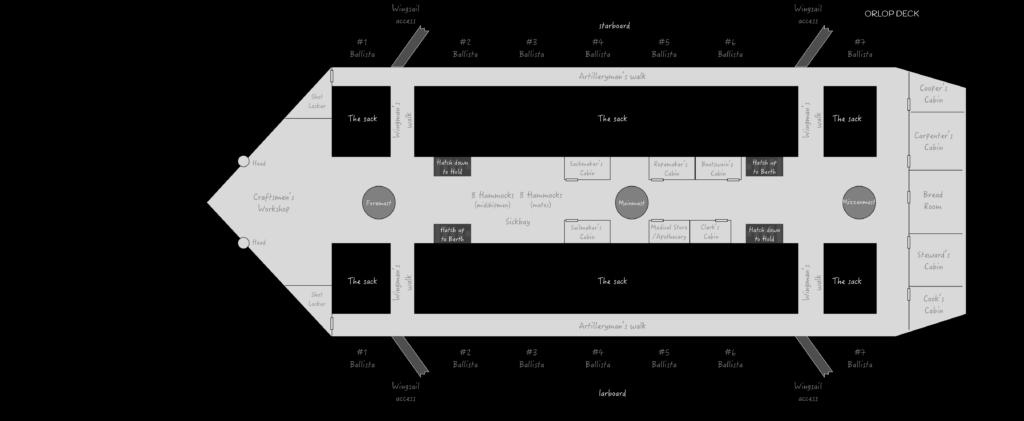

Descending yet another level, we come to the orlop deck.

On an airship, the orlop, arranged around the sacks which keep the ship aloft, is necessarily something of a patchwork space. Cramped and dark, it receives light only from the side ports (when open) and from lanterns; fear of fire aboard ship requires airmen to keep these lanterns small and protected by thick panes of glass.

Again, this deck’s fighting artillery consists of ballistas: the tight quarters prevents the use of long-armed trebuchets. Airmen must replenish the small shot lockers regularly during battle.

The orlop also houses a space for the midshipmen’s berths, which doubles for a surgery when necessary (a common practice in the Age of Sail), along with several cabins, such as those for sailmaker, sackmaker, carpenter, and ship’s clerk.

A couple of notable details on this deck. First, the two heads. In an old sailing ship, this convenience would actually be mounted into the ship’s forecastle (you can see this dramatized rather alarmingly in the film Master and Commander: Far Side of the World). In this one respect, my world affords what might be considered a slightly more dignified option.

The other notable element is the access points to the wingsails. Of course, as with all sails, sailors need to manage these, and while windlasses inside the ship handle a certain amount of this work, men frequently have to step outside the relatively safe confines of the ship’s hulls in order to make adjustments or repairs.

Hold

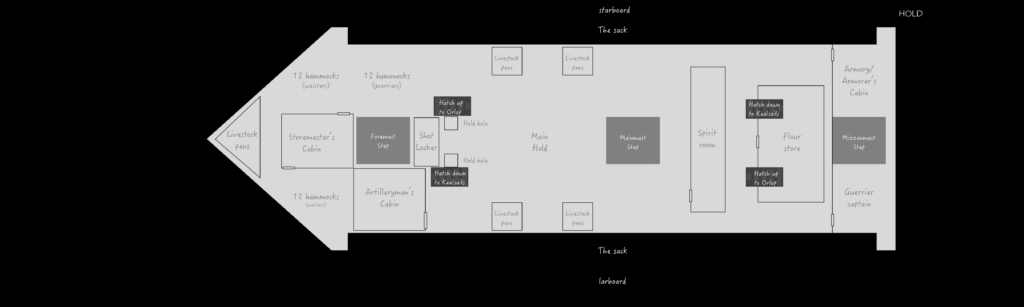

Finally, the hold: the dungeon in Harald Jorem’s belly. Just like holds of old, this is arguably the most important and least desirable station aboard ship: dark, smelly, cramped, stuffed with critical supplies, and an absolutely unpleasant place to live and work.

Of course there’s a lot of space down in the hold for general storage, but also particular places for shot, spirits, livestock, and flour, together with a few more cabins.

Here you’ll also find the berths for the waisters, the least-skilled crewmembers aboard, whose job mostly involves shifting barrels or pulling on lines. (For those who might appreciate this distinction, note that for the purpose of my story I’ve combined “waisters” and “holders” into a single role.)

Hold holes provide a spot to dump garbage and function as alternative heads.

There’s also access to the keelsails, a set of sails particular to airships which serve a function essentially the same as the keel aboard a sailing ship, except that they, like all sails, require more attention and manpower than would a conventional keel.

Set a course for adventure

Again, none of this details what A Philosophy of Air is truly about. But hopefully it’ll help some folks appreciate the depth of thought that goes into crafting a believable setting within a fantastic world.

Having all this detail has helped me consider a range of questions. For example, how well am I introducing my audience to the parts of the ship? What do they understand; what should they understand; or need to understand? What level of privacy is possible; if I need a private conversation, where could it take place? How well have I conjured this world? What are the sights, sounds, smells, textures…even tastes…of the different decks? What does it feel like to ascend into the tops, or hang from the keelsails below?

To me, whatever the deep human or philosophical questions the story delves into, these details represent the canvas onto which I paint.

I write about writing and about my work-in-progress novel, A Philosophy of Air. If this interests you, please consider subscribing.

You can also follow me on Substack.

Leave a Reply