Compass, latitude, longitude, and dead reckoning

Welcome! My name’s Marc and I’m writing a fantasy novel called A Philosophy of Air.

Picture Master and Commander or Pirates of the Caribbean meets Game of Thrones…in airships flying a thousand feet above a sea of acidic clouds.

In this series, I invite you to join me on my worldbuilding journey as I describe the Archipelago, where A Philosophy of Air takes place.

The Age of Sail heavily inspired this world. As such, much of that worldbuilding corresponds to the details of how ships of the 17th–19th century ploughed the seas.

Navigation

In the modern era, we’re blessed to have a slew of technological tools for finding our position and then figuring out how to get where we’re going. As long as I have a working internet connection, I’ll never get lost. But before mobile phones and GPS, radar and sonar, sailors had to find their way using far more elaborate and work-intensive tools.

For much of the Age of Sail, navigation was more art than science, leading to endless inconveniences, including lost ships and horrific wrecks. In today’s entry, I’m going to talk about some historical common navigation techniques and how I’ve adapted these to a world of airships.

Direction

Navigation begins, naturally, with knowing which way you’re pointing. In our world, the Chinese first discovered the principles of magnetism and used these to create compasses by at least the 11th century, and such compasses were available in Europe by 1300.

The sailors of the Archipelago certainly understand and leverage this form of navigation.

Maps

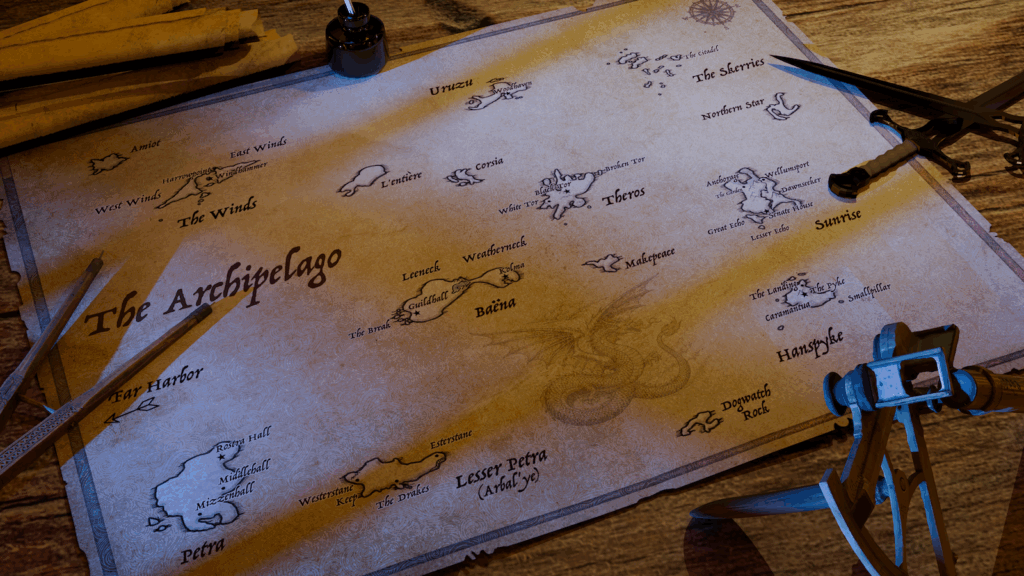

The next essential tool is a drawing that lets you understand your direction relative to a known frame of reference. Stated simply: a map.

Obviously, the people of the Archipelago understand and use maps. Honestly, it’d make a pretty poor story if they didn’t. I’ve posted the world map before, but here it is again for your reference.

Calculating latitude

Here’s where things get interesting.

The next problem relates to understanding your position on an actual fixed scale. We use degrees of latitude and longitude for this.

Latitude — your north-south location — is fairly easy to compute at night…assuming you can see the stars. Again, the principle is ancient, going back at least to the ancient Greeks. The common method is to use the angle of a known star relative to the horizon. Polaris, the North Star, is the typical reference point in the northern hemisphere since its position isn’t affected by time of day or longitude.

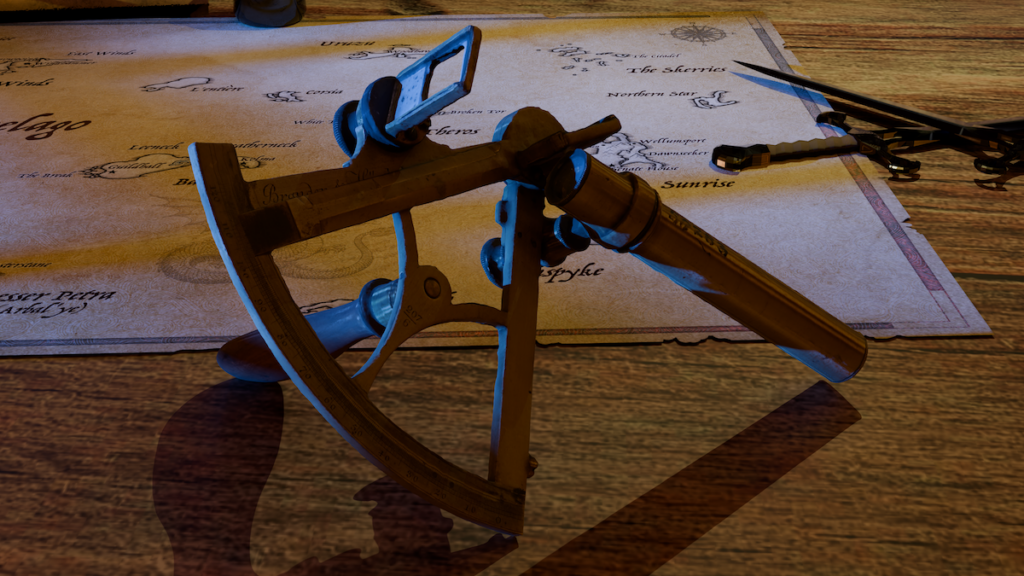

In the Age of Sail, tools like the quadrant, octant, or sextant (and before those the astrolabe, backstaff, or a device called a “kamal”) were used to make the necessary calculations.

Over the centuries, such devices evolved by necessity: as explorers journeyed further, they required ever more sophisticated tooling to make effective calculations.

As the Archipelago encompasses only a relatively modest percentage of its globe, I’ve speculated that the forces driving my world’s navigators never forced them to innovate in the same way. Thus they use quadrants, a relatively primitive version of this method.

Calculating longitude

It turns out that longitude is harder to compute…much harder.

At root, the problem of longitude rests on the fact that the Earth rotates east-west. One may use the stars to fix a north-south position, but when you’re attached to a spinning globe (shut up flat-Earthers, you’re wrong), one’s east-west position shifts constantly.

One can fix an east-west position with a very accurate clock…but highly accurate timekeeping devices are a modern invention. John Harrison developed the first such device only in 1761.

Via Wikimedia. Photograph by Mike Peel.

It’s hard to overstate just what a huge problem this was for mariners. In bad weather, a miscalculation of position could cause a ship to drift out to sea or smash into a jagged coastline. In fact, in 1707, a miscalculation of longitudinal position led to a naval disaster at the Isles of Scilly that wrecked four men-of-war, killing somewhere between 1,400 and 2,000 sailors.

Via Wikimedia. Author unknown.

Harrison’s highly accurate timepiece (a timepiece that resisted the many complicated inconveniences of a ship’s motion, water, and salt) revolutionized the sailor’s ability to compute his position.

The airmen of the Archipelago have a similar constraint: a preindustrial society, they lack accurate timekeeping devices and so are very much guessing when it comes to both time and longitude.

As a footnote, I’ll mention that the journey that led to accurate computation of longitude is fascinating. If you want to dig into it I recommend Dava Sobel’s book, Longitude.

Dead reckoning

The absence of an ability to plot position perfectly leads to one of the most fundamentally important forms of navigation used in the Age of Sail, one very much employed in the Archipelago: dead reckoning.

It’s a useful concept. Simply put, if you can see and recognize a stretch of land, you know your position. If you can’t see it, you calculate based on your last known fixed observation.

This comes with a couple built-in problems.

“Hey John, that’s Point Hope right there.”

“No, Pete, I’m pretty sure it’s Cape Despair.”

Even if you can see what you’re looking at, it only helps if you can actually recognize it. When you can’t see it, matters get even worse.

At sea and out of sight of land, a ship relies on those latitudinal and longitudinal calculations, which as we’ve noted can’t really be relied upon. So you also keep a record of that last known position, along with your course and speed. If all your measurements and maps and logs are perfectly accurate, great! You’ll know your position.

In reality things don’t work that way. Measurements of wind and water speed were far from perfect. Currents could move in unexpected ways. A storm could easily blow you off course. Poor visibility might disguise what you think you’re seeing. If you mistook Point Hope for Cape Despair, you might not even be calculating relative to the correct initial location.

A running joke among sailors is that there’s a reason they call it “dead” reckoning!

Ship’s log vs. kite and fettle

Here’s a fun invention I came up with for the story: the kite and fettle.

During the Age of Sail, a ship’s speed was determined by throwing a log overboard. The log, attached to a knotted rope, drifted behind the ship over a fixed period of time and a crewmember counted the knots as the rope paid out.

From Wikimedia. Author Rémi Kaupp.

As an aside, this is where we get both “log” as in “Captain’s log, stardate, etc.” and “knot” as in, “ship’s speed is six knots, sir.”

Of course dropping a log into the ocean kind of requires, y’know, an ocean. So how do sailors estimate a ship’s speed in a world where the “ocean” is a sea of acidic clouds?

Airmen use a kite and fettle.

The fettle is a spinning sail like a pinwheel, typically set up near the binnacle (where the compass lives), which pushes sand as it turns. The amount of sand yields a measure of the ship’s speed relative to the wind and its direction relative to the ship itself. This provides a relative measurement of ship’s speed and wind direction.

A kite is simultaneously let out on a knotted cord, allowed to fly freely. Just like the Age of Sail log, knots are counted over a set time period to establish the wind’s independent speed and direction. Taken together, these two readings allow a (very) rough sense of the ship’s movement, offsetting windspeed and direction.

The costs of failure

As was historically the case, the price an airship crew of misunderstanding their position is exceptionally high.

Take another look at the map above. Imagine miscalculating one’s position by just a few miles. You might bypass your destination in a storm when visibility is low. You might wander into unfriendly territory and be set upon by pirates or enemies. Or you could wander out into the vast, unknown sea of clouds and whatever unspeakable terrors exist beyond the known horizons of the Archipelago.

How this fits into the story

In truth, navigation is just a corner piece of my actual story. Philosophy isn’t about navigation…it’s not even really about airships, even though they’re a centerpiece of the fun.

Still, understanding the particular difficulties which sailors of my world experience allows me to create interesting background activities and creative conflicts for them to encounter. It’s all part of the texture of this world. It’s a very small piece of understanding the larger world my characters inhabit and why that world is — I hope — worthy of your attention.

I’m currently writing A Philosophy of Air. Please consider subscribing to my blog to follow along.

You can also follow me on Substack.

Leave a Reply