It has to be this way — not just in drama, but in life

Every decent writer knows that there’s no drama in an overpowered hero for whom everything is too easy.

Look, up in the sky!

Just look at the most overpowered hero in the history of storytelling: Superman. Go back and read the earliest Superman comic books; they’re mind-numbingly dull. Ordinary bank robbers and thieves stand no chance against a guy who can fly and lift a battleship, a guy who can’t be hurt. Outcomes are never in doubt. It doesn’t take long for the gag to wear thin.

Eventually, the comic book’s creators wised up. Before long, Supes was fighting robots and mad scientists, then super-genuises and villains with superpowers to rival his own.

When the Man of Steel is most dramatically effective writers force him to contend with the same frailties we all share: perils not physical but emotional and thematic. While super, our hero has known loss. In some tellings, his power makes him an eternal outsider. Who cares if you can leap tall buildings if you can’t save the people you love? What does a hero do when faced with those who reject his help?

So why do we insist on everything being so hard? Writers have absolute control over their creations. Why don’t we just wish fulfill our way to easy victories?

Good guys and the truth

Murderers and thieves and abusers exist in Metropolis and in real life. Why not just have Superman get rid of them? Corrupt, powerful people run companies and governments. The last son of Krypton should be able to manage that in an afternoon.

Intuitively we all know why it can’t be done this way: magic answers and easy fixes are boring. We want to be entertained, and we expect the storyteller to craft a difficult challenge and then ask our hero to meet it in entertaining fashion.

But there’s a deeper level to this question, which is that we also know it’s not true.

What do we mean by “true” when we talk about fiction, and especially science fiction, fantasy, and related genres like superheroes? By definition, these aren’t things which exist. We’re not talking about literal truth but rather things that ring true, things that, while fantastical, reflect the common reality we understand. Even fantastical drama must ring true in this deeper sense.

Knowing that bad things happen, that bad people exist, it rings intuitively off-key for those problems to simply vanish.

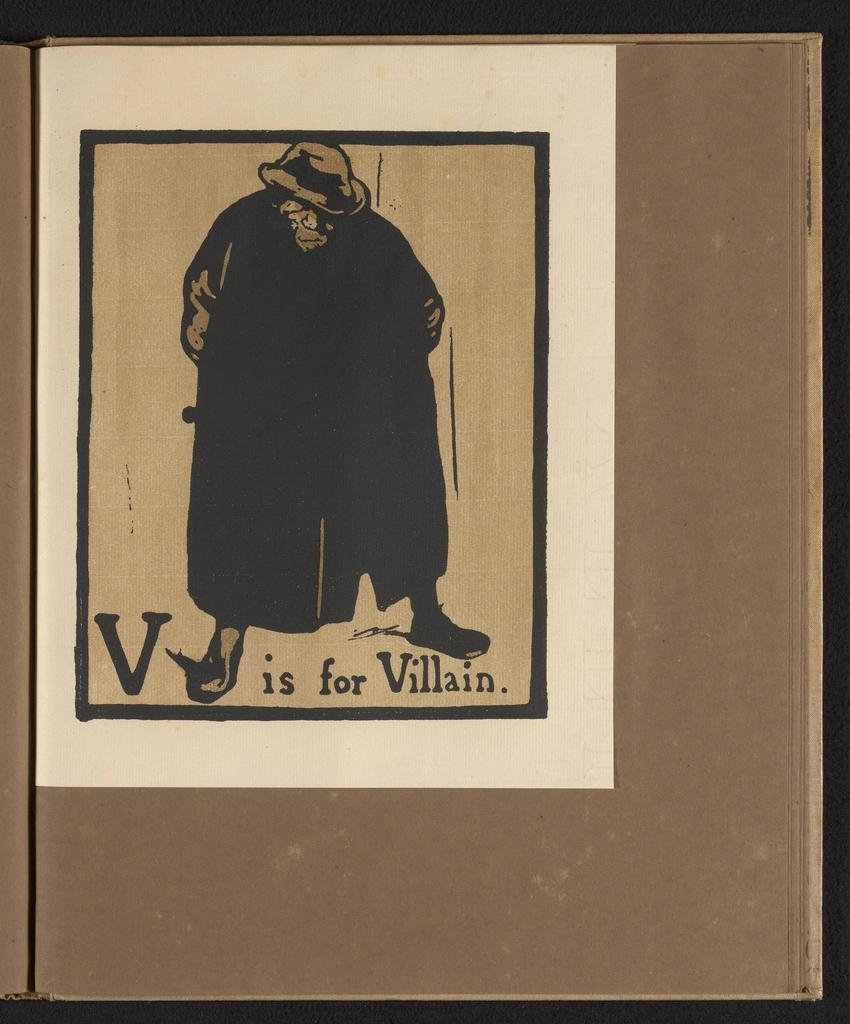

The villain’s challenge

We know the features of the villain. Villains lie. They cheat, kill, and destroy. They seek what’s good for themselves and try to sever the bonds that hold the rest of us together.

In most dramas, the villain wins for at least part of the story. He kills some people. He gains power for a time. His actions pressure the good guys, often straining their relationships to the breaking point. Again, this is dramatically necessary: it allows the emotional buildup and release we expect from a narrative.

At the same time, we recognize the underlying truth: no great move forward comes without powerful countervailing forces.

But the villain’s challenge is easy. Being the villain, he needn’t necessarily follow a moral code. He probably doesn’t care who he sacrifices, so long as he achieves his ambition.

Note, however, that a well-written villain can make us care about them precisely by breaking from this template.

The hero’s job is much, much harder. It has to be. The curse of being the good guy is that on top of your explicit objective, you’re tasked with maintaining order and integrity. If you achieve your objective by sacrificing too much, you’re no longer the good guy…if too many people are hurt, or if you sacrifice your core values, you may restore order, but you’ll know in your heart — and the audience will know — that you’ve failed.

Good guys and bad guys in our midst

I’m going to apply this to our current political moment.

Now, I’m not given to making my blog about politics. While I certainly have my opinions, I’m really here to talk about writing. But there are few fictional dramas that compare with reality for making this particular point.

In the United States today (and painting with an absurdly broad brush), there are two national movements. One fundamentally wants to bring people together, wants everyone to share in the nation’s prosperity, wants to strengthen pluralism and cooperation. The other focuses on excluding people, denying objective truth, sabotaging institutions, and protecting the ultra wealthy.

Your politics may differ from mine. Honestly, I don’t care. What matters is the good guy/bad guy story this tells.

Bad guys divide and destroy. Why? Because it’s in their interest. And because it’s easy. They can scream “government is corrupt!” They’re not wrong…you’d have to be pretty naive not to see that this is objectively true. All large organizations contain corruption. But what’s the answer to that problem? The bad guy…the snake oil salesman…goes for the easy answer: “destroy the corrupt thing.”

tearing things down is easier than the hard work of building.

Having brought down that corrupt thing, however, it transpires that alongside the corruption a lot of important work was being done. The “bad” system removed, our villain now has free rein to exercise corruption for his own benefit.

This isn’t fantasy, it’s history.

The good guy’s challenge

The good guy, as I’ve said , has a far harder problem. First, he has to accept the kernel of truth in the bad guy’s fiendish plan (remember, no convincing villain can be 100% wrong). Then he has to see the better answer. Finally, he has to run the gauntlet of the bad guy’s schemes and henchmen to realize that answer. To make things really challenging…especially in real life…he has to convince others to see past the easy answer.

To see past the comforting lies.

Along the way, the good guy probably has allies who betray him. When I described our political situation above, you might have thought, “That’s ridiculous! There are plenty of politicians in movement A who do what you say describes movement B!!” You’re right! Life (and good drama) can be messy. That doesn’t make the observations wrong.

It simply makes the hero’s job harder.

Rising to the challenge

The good guy has the harder job. He has to. These are the rules.

I don’t know if dramatists have always understood this intellectually or if it was simply a gut instinct, but whether struggling against gods and monsters, rivals, or their own inner demons, the hero must always start overwhelmed, and then rise to meet the challenge.

And so must we.

I write about writing, mostly, and about my work-in-progress novel. If this interests you, please subscribe to my blog, share with others, or follow me on Substack.

Leave a Reply