(Part II of II)

My name’s Marc. In this series, I’m guiding you through my worldbuilding process, exploring the steps involved in creating the amazing and fantastical world of the Archipelago, the setting for my naturalistic fantasy novel, A Philosophy of Air.

Picture Master and Commander or Pirates of the Caribbean meets Game of Thrones…suspended a thousand feet above a sea of acidic clouds.

Last time, I explained how airships in my world stay aloft. If you missed it, go and check out that post. I’ll wait. This time, we’re going to discuss how a ship, now essentially weightless, moves about with the wind.

As I’ve mentioned before, my story is heavily inspired by the Age of Sail. In that glorious era, floating death boxes™ contained essentially imprisoned men who admirals, captains and lieutenants [LEF-tenants if you’re English] inspired to beat the crap out of men in other floating death boxes™ until one side should either sink, surrender, or be boarded. Ships of that era had no engines. Everything relied on skillfully handling a complicated array of sails along with a tiller.

On an airship, tillers makes no sense. With no power driving you but the wind itself, everything has to be managed by deflecting passing air off a surface. So there are more sails and more types of sails. And it’s through the use of these sails — some which match those in our world and some of which I had to invent for my story — that our airships move.

Before we set sail…

…a reminder: as I mentioned in my prior post, this is not a science lesson. This is a fantasy story and I’m asking…nicely…that we respect the idea that if some stories can have talking animals…

…multiversal travel…

…wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey conundrums…

…or frakkin’ zombies!!!!

…maybe it’s not too much to imagine a world where my cute, imaginary airships are just a fun, metaphorical convention to discuss something interesting.

OK?

So, sails.

While the airships in A Philosophy of Air can have a huge range of configurations, I’m going to discuss a common setup which applies to the most important ships in my story.

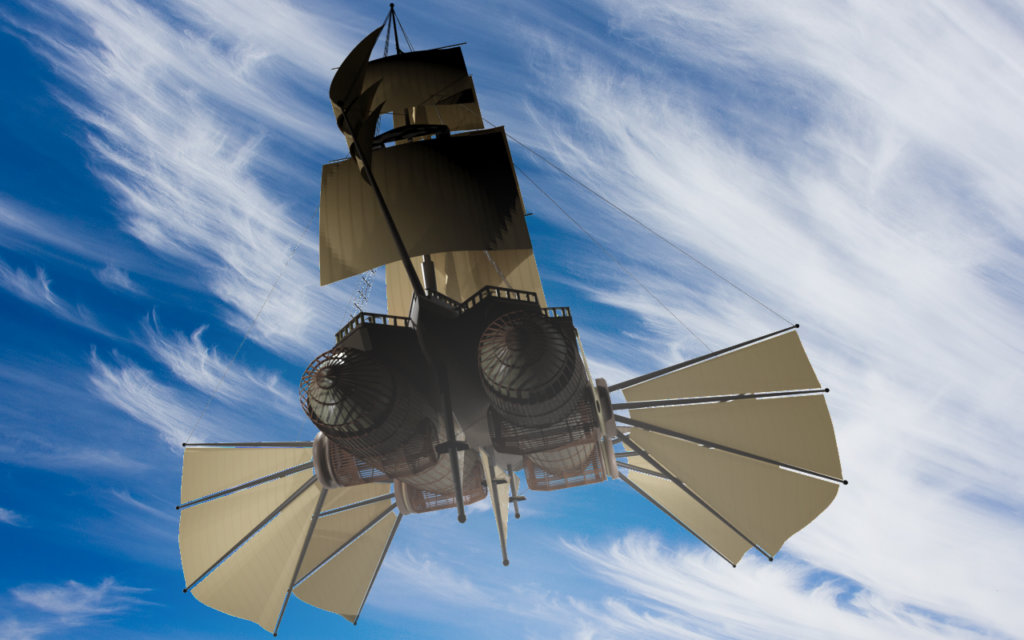

Here’s a model I created in the 3D app Blender which was super helpful for me to conceptualize how my ships work.

This doesn’t represent any specific vessel in my story. It’s a mishmash of ideas. But it’s good enough to illuminate how sailing works.

Side note: I’m not an artist, but designing a 3D model turns out to be an amazingly useful worldbuilding activity. (If you’d like me to write a post on how I created this in Blender, please let me know!)

While the Archipelago is the literal world of my novel, the practical reality is that much of my tale occurs within the confines of an airship. If I’m to tell a great story, I’d best understand those confines very, very well. Building a 3D model, along with deck-by-deck schematics, forced me to precisely name and understand a whole range of little details. How tightly packed are the sailors? Where do they keep provisions? Or eat? Or poop? What are the precise names for each mast, spar, rope, railing? In which ways are all these things the same as on 18th century sailing vessels; in which ways are they different?

A note on pronunciation

Sailors in the days of Jack Aubrey wouldn’t typically say “mainsail” or “studding sail” the way you or I might pronounce it. These were terms of art, as particular to their world as three-letter acronyms are to today’s tech bros. Terms were typically truncated, so mainsail became “mains’l” and “studding sail” became “stuns’l.”

In the book, I’ve largely opted to maintain proper spelling, but when these words appear in dialogue, I’ll spell them to align with that historical pronunciation, and I’ve maintained that pattern with newly-invented sails, too. So a “wingsail” becomes “wings’l” and “keelsails” become “keels’ls.”

Adapting sails from naval tradition…

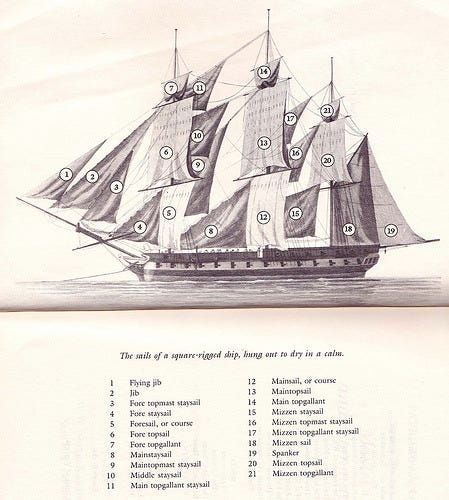

The sails on top of the vessel are exactly the same as those on a classic sailing ship in the real world. There are three masts: fore, main, and mizzen. I won’t name every sail for you here, but things a sailor of the era would expect to see are present, like mainsails, topsails, studding sails, spankers and jibs.

…plus all-new sails unique to airships

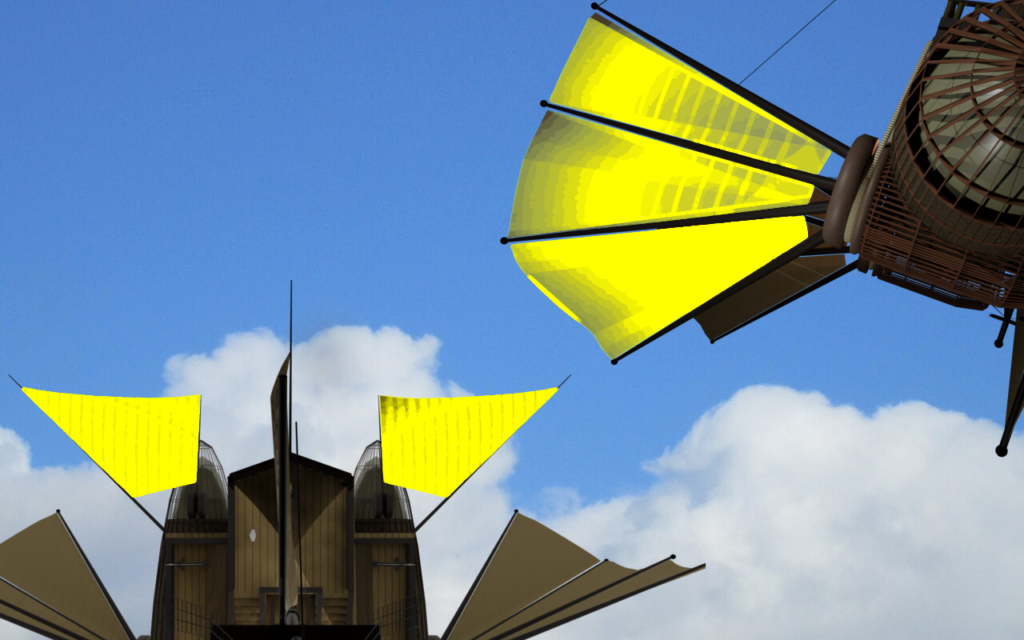

But as I suggested above, airships require still more sails, those which a ship in the air would plausibly require. Wingsails assist steering. Tailsails allow our buoyancy-compensated ships to gain or lose altitude.

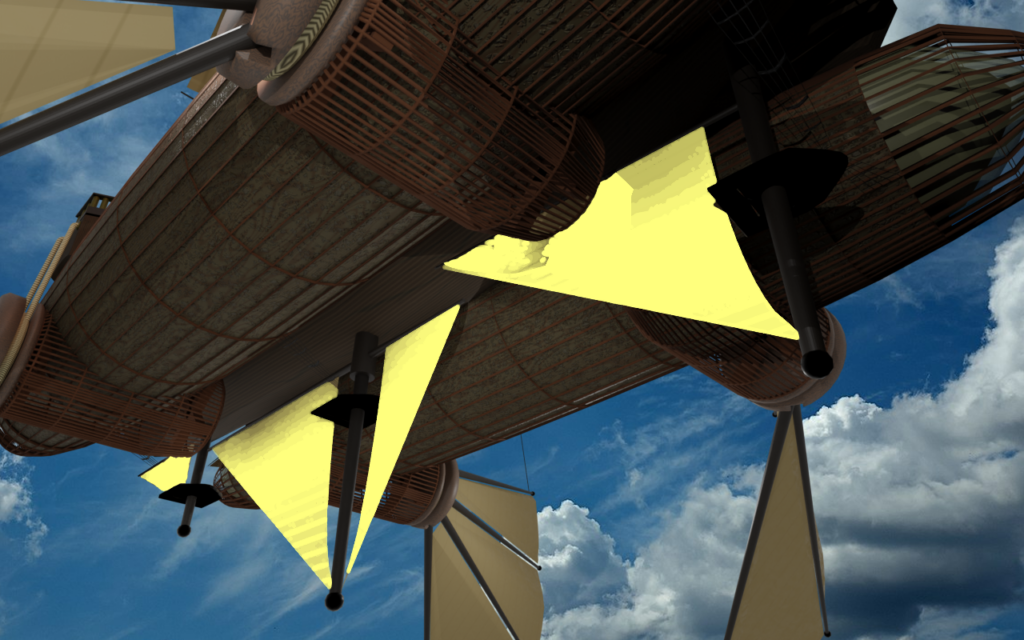

Less intuitively obvious, keelsails below the ship break up the flow of passing air. This admittedly fanciful idea simulates the differential pressure which water creates on a classic ship’s hull and keel. Without something to create such pressure, ships could never move in any direction other than straight downwind.

Keel masts are retractable. When an airship lands, the crew drops lines to dockworkers, unbends (removes) the sails, and hoists up these masts, allowing ships to moor.

Finally, we have catchsails. You’ll have to make do with my description of catchsails, as I’ve never gotten around to rendering this detail. (Sorry!)

Crews deploy catchsails only when a ship sails close by the wind. Wind-powered ships can never sail directly into the wind, but in the water they can approach an upwind destination by tacking across the wind, working that direction with multiple left-and-right switchbacks.

In my story, catchsails help this process. Hung between bowsprit and wingsail, these sails “catch” the wind and deflect it, focusing just enough energy to allow a ship to tack upwind.

Another aside: did you know that when we say that something works “by and large” we’re actually referencing a bit of sailing terminology? Sailing “by the wind” means sailing upwind. Sailing “large” means sailing downwind. Thus, anything that works “by and large” works in most situations.

Sailing hazards

There are, of course, some forces in the world that my ships can’t fight.

For one thing: calm weather. In ocean-going sailing ships, it’s not unusual for a ship to be “becalmed” and left to drift until the wind picks up again. One famous sea lane near the equator was called “the doldrums.” Winds often fail in this part of the world, leaving ships stranded until the wind picks up again. This same hazard is possible in my world.

On the other end of the spectrum, an airship is very much at the whims of the weather. A heavy wind may be impossible to manage and sailors may struggle for days against a fierce gale, making no headway at all, merely hoping not to be blown into uncharted territory.

Nearly as bad, even a storm with winds in one’s favor may cause one to lose one’s position. We’ll get to the tools of navigation in a future post, but suffice it to say that it’s VERY easy to get lost at sea in the Archipelago.

Set a course for adventure…

So there you go. Between the last post and this one, you can now see how ships work in my world, along with a sense of my internal logic. Let me know what you think in the comments. I truly do welcome all well-intentioned feedback.

Until next time, my friends.

I write about things which interest me. I’m living in France at the moment, so maybe I’ll write a bit about that…but most of my articles are about my work-in-progress novel or about writing in general.

If my ramblings interest you, please subscribe. You can also follow me on Substack.

Leave a Reply