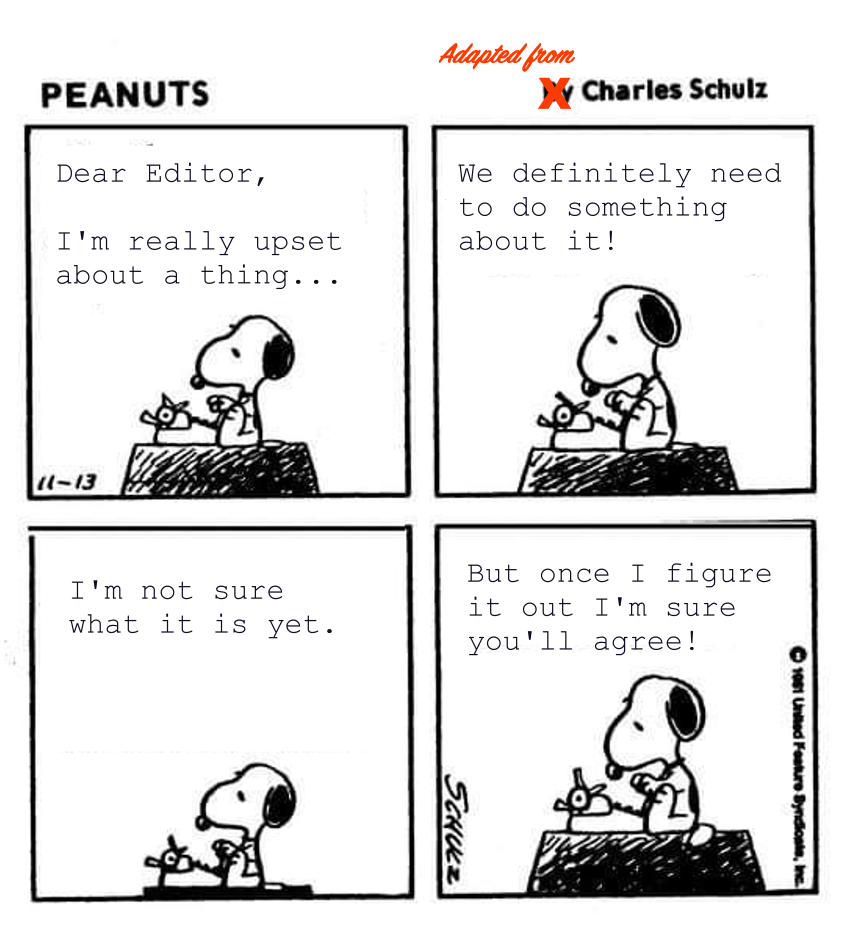

Your friend tells you “I’m writing an editorial for the Times.” You reply, “Cool! What’s it about?” To which they respond, “I don’t know. I’ll figure it out as I go.”

That’d seem odd, right? Wouldn’t you expect anyone writing an opinion piece to know what it was about before they began writing?

But this is exactly how so many people go about constructing novels and screenplays. In fact, there’s a line of advice out there — and I’ve heard it many times — that says, “just write your story…your theme will emerge as you do.” According to this model, once you’ve written your great story, all you have to do is examine the plot, figure out what it’s really about, and then sand off some rough edges.

Hey presto, THEME!

This notion treats theme like window dressing. Like an elegant flourish instead of the core of your story.

I think this is backwards and presumes that you have nothing of importance to say. You’re just writing a fun story about space wizards or zombie cowboys or about that summer when you found a body while hiking in the Sierras. That your story is about the plot.

“If your story is about what it’s about…”

Those who’ve read my prior posts know that I go back to this bit of advice by Robert McKee all the time:

If your story’s about what it’s about, you’re in trouble.

Your story, long or short, fiction or nonfiction, is simultaneously about two things: plot and theme.

Plot

This is what you’ll usually tell your friends or the guy on the street who asks, “What’s your book about?”

When people ask about my work-in-progress novel, I begin with something like:

It’s about a world where airships battle above seas of acidic clouds, about the outbreak of war, and about a young man with the potential to change everything through science and reason being forced instead to fight for a navy as cruel and oppressive as those they’re fighting.

That’s mostly plot. I’m describing the world and what happens in it (hopefully in a way that sounds exciting) and nodding to my main character and his core conflict.

But this isn’t really what A Philosophy of Air is about. Which brings us to…

Theme

Notice the last bit of my description:

…a young man with the potential to change everything through science and reason being forced instead to fight for a navy as cruel and oppressive as those they’re fighting.

The bold-faced elements hint in the direction of my theme.

Authors often don’t like to explain our theme baldly. First, it kind of ruins the surprise, the fun of the audience discovering what you’re really getting at. Also, being explicit about it often makes it seem somehow less clever, as if all your brilliant insights can be distilled into a single sentence.

So without utterly spoiling my deep and thoughtful novel, I’ll just say that what my story is really about has a lot to do with understanding who your enemies are; about how a person you disagree with might still be a potential ally, a question highly relevant in our world today.

Theme is what your story is really about: the core, universal topic you want to examine through the lens of plot, character, and setting.

The advice to just start writing, hoping to discover the theme as you go might eventually (after countless rewrites) get you to your theme and a story which supports it, but it’s a weak approach and at best the long way around.

How is theme exposed?

Theme isn’t just some catchphrase dropped into your story. It’s the point you’re trying to prove.

Your story is like the editorial with which I introduced this post. Just as every sentence in an editorial exists to argue in support of the article’s theme, each element of your story — each character, each scene, each conflict — should somehow reinforce the argument you’re making.

Trying to shoehorn in a theme after having constructed your plot is therefore like building a home from the roof down. Like trying to find the point of the editorial after having written it.

When theme comes to town

In the very earliest days of developing your story, you might think about a question you want to examine, a core human struggle you want to comment on. Or you may think of a team of flying ninja teddy bears defending the world from Lintotron the Destroyer.

I’m more Lintotron-oriented myself. Plot and character and title ideas usually pop into my head way before I think, “Ah, Lintotron represents our inability to deal with the loss of childhood. The teddy bears demonstrate our struggle to maintain that spark of innocence in our tortured lives.”

So I’ll cobble together the scattered pieces of my story, genre, environment, and character, and then “discover” my theme. But I try to do this by the time I’ve broken down my anchor beats.

For those who don’t care to read my post on anchor beats, these are the story’s five critical moments, the ones where my main character faces her most crucial tests.

- Catalyst (aka Inciting Incident)

- Break into Two (the hero decides to embark on adventure)

- Midpoint (a false victory or defeat changes the course of the adventure)

- All is Lost (the hero might lose everything…)

- Break into Three (…but there’s one more chance)

In the plotter-oriented approach to storytelling, I assert that you should lock in these five events early. And if all five aren’t tightly tied to the theme, if they’re not supporting or challenging your core assertion, then you don’t yet understand the story sufficiently and need to rethink.

Having established that the theme and anchor beats are well aligned (and importantly that my main character and their antagonist(s) are good fits for this theme) I can then add in all the other story beats and scenes which continue to test and support my case.

Theme, articulated

In the Save the Cat methodology, one of Blake Snyder’s fifteen key beats is “theme stated.” Somewhere in the first act of your story, you’re supposed to explicitly say out loud. “This is my theme!”

Of course when this is done well the audience barely notices it. Done poorly, Uncle Ben intones “With great power comes great responsibility!” And it becomes a running gag forever after.

I don’t even think it’s necessary to state the theme in dialog. Particularly in film, one could imagine simply seeing an image which somehow expresses the theme. In fact, Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo more or less does this with its repeating spiral imagery.

I’m not actually suggesting that you have to have a clearly articulated version of your theme before you get to writing. This isn’t a high school thesis paper, and I’m not your composition teacher. The elegant version will come to you as you write.

What I do recommend strongly is that you have a very strong sense of what you’re really writing about, what your theme is, and that your anchor beats, your characters, your setting and conflict all support that idea before you begin writing in earnest.

With this as a strong foundation, you’ll know with each element whether you’re contributing to your story or distracting from it.

It’s about…time to wrap this up

What do you think? How much do you focus on theme? Do you come up with your premise first and then find the theme? Or do you begin with something you’d like to talk about and then find the story to fit that thing?

Tell me about it in the comments.

A Philosophy of Air is my work-in-progress novel. It’s the first volume in the series The Poison Sky.

My blog deals with a variety of topics which interest me, including language, writing, and the city of San Francisco. Please consider subscribing. You can also follow me on Substack.

Leave a Reply