Let’s talk about contrast. About why “big” isn’t better. Why “different” is better.

I recently attended a writing workshop – I won’t mention whose – where the teacher espoused the virtues of amping up every scene. “Make every scene bigger than life,” we were told. “No one wants to read reality. They want a stylized version of reality that’s bigger than life.”

In my view, this is both useful and terrible advice.

If everything is big, is anything big?

I agree that no one wants to see reality.

Even the reality of the most amazing person on Earth largely consists of them waking up, going to the bathroom, making coffee, eating breakfast, heading out the door…oh look! a meteor just fell from the sky! The audience has nodded off waiting for the interesting bit. Stories by their nature are stylized distillations – the “good bits” version of the overall narrative, whether “real” or fictional.

(I’d also question whether it’s even possible for a writer to create anything truly “real”…but that’s a different blog post.)

So it’s good advice to select the important scenes and make some of them bigger than life. To find the drama in the story and selectively amp it up. By all means, make big moments big. As big as you can and as the story will allow.

But should every scene be bigger than life?

A few of my favorite things

Variety, as they say, is the spice of life!

No single note can make a song. No single brush can paint every picture. Nor can a single flavor satisfy our palates. Variation is what makes all these things possible.

Love of variety powers stories as well. Not simply the different genres – there certainly are folks for whom science fiction or romantic comedy or period dramas are their “favorites” – but the internals of stories. Variety isn’t simply a matter of differing tastes, it’s an inherent need for the vast majority of humans.

We need variety…contrast…to maintain interest.

Contrast is king

Songs have verses and a chorus, usually with two different, complementary musical signatures. Variation keeps them interesting. Even paying attention to the emotional resonance of two adjoining notes shows the value of contrast. Consider the opening line of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” from The Wizard of Oz to hear how contrast sells the emotion.

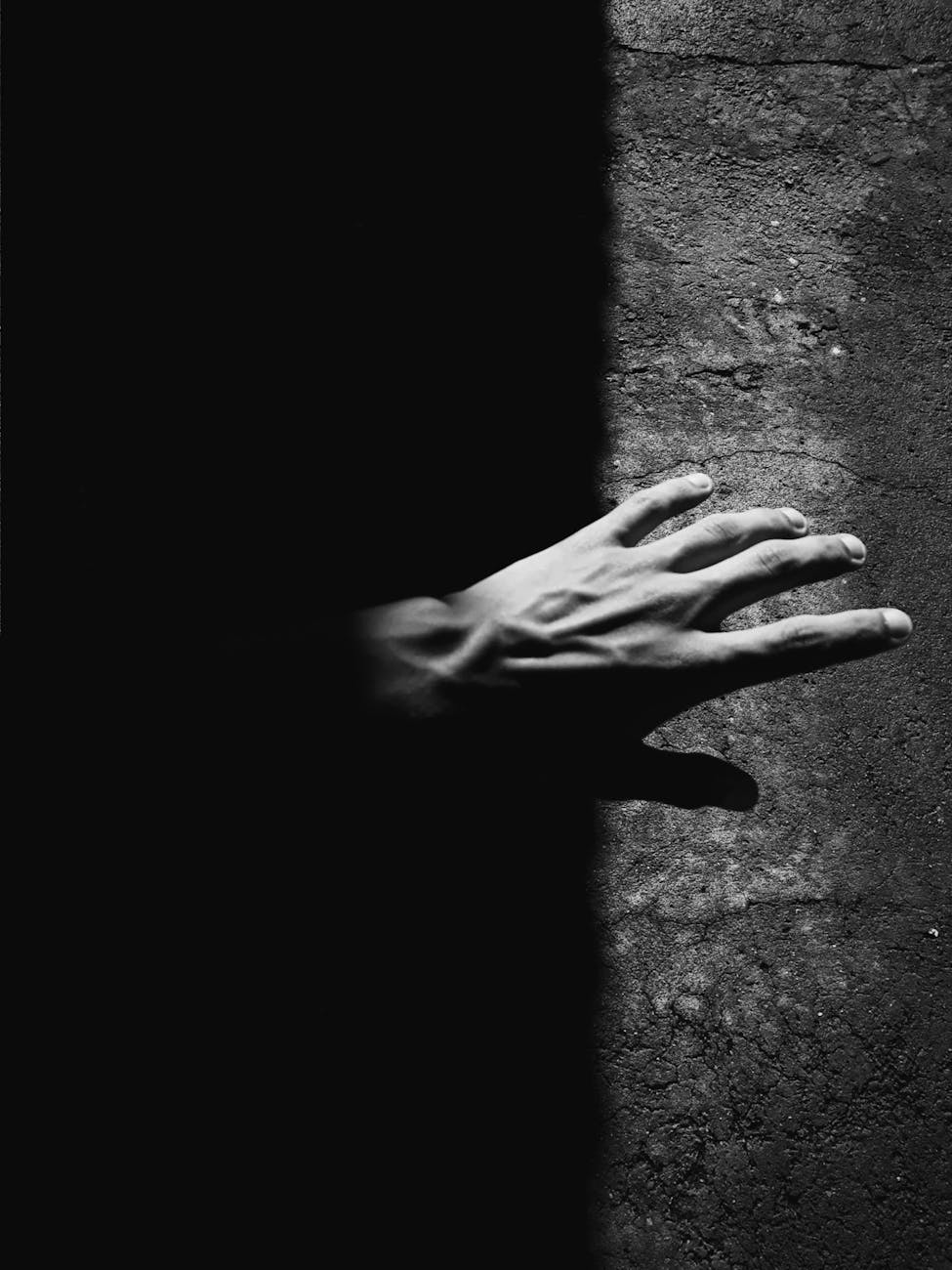

The art technique of chiaroscuro employs sharp contrast between dark and light to capture attention and guide the eye.

Contrast this against – and I’m sure we’ve all experienced this – a speaker who delivers his information in a droning monotone. However captivating the content, there’s no joy in hearing the same note struck over and over again.

Variety maintains interest.

Watch your favorite movie. Read your favorite book. I can almost guarantee that you’ll observe big, in your face moments contrasted against smaller, quieter, introspective moments. The volume will suddenly jump or suddenly go quiet. Big action or conflict will juxtapose personal emotion or reflection. The meaningful will smash against the silly.

Ben Kenobi dies, then Luke takes a quiet, reflective moment to mourn him before leaping into a battle with Imperial TIE fighters. Loud. Quiet. Loud.

Scout, Jem, and Atticus confront racist townsfolk, then quietly walk home, the “big” moment being when Atticus tousles Jem’s hair. Tense, then comfortable and heartwarming.

Master (and Commander) of contrast

Here’s an interesting example: in Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World, the movie’s theme is introduced as a truly terrible pun: “the lesser of two weevils.”

The utter silliness of the joke (itself contrasting near total silence with uproarious drunken laughter), and the relatively mundane nature of the scene itself, contrasts strikingly with the series of big set pieces where we observe how “the lesser of two evils” is no laughing matter in Jack Aubrey’s world. Boys will be disfigured, men will die, battles will be lost and won, all in the service of playing the inexact game of deciding what to gain and what to sacrifice.

Placing the film’s harrowing theme statement within a “dad joke” over dinner heightens the ultimate irony of what follows.

Contrast in characters

By the way, this same principle of contrast applies to characters: variation between characters makes each more interesting. And the inconsistencies, foibles, and hypocrisies within individual characters likewise gives them important, memorable texture.

This can be overdone, of course. Perfectly contrasting characters may end up looking like cardboard cutouts: perfect heroes facing off against cliched, mustache-twirling villains. Inconsistencies within a character may feel illogical. Part of your job as a writer is to draw the contrasts as broadly or as finely as your story dictates. And while others can advise you, you’re the only one who can ultimately make that determination.

Contrast is key, but no principle is perfect. How cartoonishly different should your heroes and villains be?

It’s not the size of the scene, it’s how hard it works

The trick is not – as the teacher in my class suggested – to make all scenes big. That’s straightforwardly bad advice in my view. Instead, make each scene work hard.

“Working hard” means that the scene, big or small, punches above its weight in terms of how it drives the story.

Big action scenes are great. Can the scene work harder by including tiny beats that reveal character, theme, symbolism, or information? Can a small, reflective scene foreshadow something larger? Is the scene, big or small, the best version to carry both what it literally describes (e.g., Atticus tousling Jem’s hair) with some point that strikes deeper (“his one gesture of affection”)?

Example: is bigger vs. works harder

To make this idea of working hard more concrete, here’s an example:

A detective interrogates a young man accused of murder. Waiving his right to an attorney, the suspect recounts his side of the story.

Nothing wrong there necessarily. This will functionally tell us about the detective, the suspect, and what (he says) happened. But we could make it bigger, perhaps like so:

A young man is dragged bodily into the interrogation room. He screams for his lawyer. The detective and his partner play good cop/bad cop to coerce him into recounting his side of the story.

This is bigger. More drama, more conflict, more tension as the good cop/bad cop routine plays out to amp up the melodrama.

How could this scene work harder?

A young man is accused of murder. The detective suggests the suspect call his attorney. Instead, the suspect eagerly tells his story. The detective notices that the young man stutters, plays with his wedding ring, and blinks at key moments.

In this version, we learn way more about both the detective and the suspect. The detective is fair (he wants the kid to have an attorney), and he’s observant. The kid’s reckless, married, has noticeable personality ticks. The top level information is identical to version one, but the scene works harder by revealing details which will pay off later.

We could of course combine the second and third versions. As a writer, your questions should be: do I want a big, dramatic scene here? If so, great. If not, great. What you always want is for the scene to work hard. To set up and/or pay off.

Work hard, play hard

Once you see your scenes working hard, organize them to amp up contrast. And organize the beats within the scene to create contrast.

Quiet to loud. Funny to serious. Epic to personal.

A big explosion at the end of a battle knocks the protagonist out. She wakes up to the now-silent battlefield, the perfect quiet broken only by a single, tweeting bird.

Years later, as she’s sitting in a cafe in Venice quietly reading a newspaper, she’s confronted by an angry soldier, a victim of shell shock, who remembers her from that conflict. She flees from that exchange to the silence of a museum where she simply walks from painting to painting…but we focus on specific paintings which stir difficult memories she’s tried for years to suppress.

Battlefields are epic. Sitting at a cafe, and looking at paintings are ordinary, mundane. But we can use the friction of contrast to create meaning and drama which compel the audience’s attention.

Contrast matters

The “good bits version” of your story needs big moments. It also needs small, intimate moments. There’s a reason for the hackneyed, old movie pitch: “You’ll laugh! You’ll cry! You’ll scream!” The film industry understands – and successful writers know this, too – that a range of emotion keeps audiences engaged. I doubt any movie ever has added “You’ll contemplate!” or “You’ll draw connections!” but good stories do these things, too.

When George Bailey hears a distant train whistle, the prior scenes have worked hard to inform us that he’s thinking of missed opportunities, of a wonderful life wasting away.

Immediately prior to Hamlet‘s final scene, the hero tells Horatio “We defy augury. There’s a special providence in the fall of a sparrow.” It’s a moment of profound contemplation…of acceptance. It tells us everything about how far Hamlet has come, and it’s usually played intensely, quietly, a contrast to the big fight scene to come.

Remember that the most mundane of scenes can be “big” when well crafted. The biggest, most amped up version of a scene can be vacuous and pointless. Don’t aim for big. Aim to deliver impact.

Whether your story is comedy, tragedy, superhero adventure, sweet romance, deep meditation, or slice-of-life, what will maintain the audience’s interest moment-to-moment and scene-to-scene is variation.

Contrast.

Please consider subscribing to my newsletter. I write on the subject of writing, about my upcoming novel, and about other subjects which you might find interesting.

Leave a Reply