“Storyboard” is part seven in my ongoing series about Plotter-Oriented writing, which I predict will one day be bigger than buggy whips! To learn more about Plotter-Oriented writing, check out this post.

Over the course of this and the next several posts, I’m going to walk through the construction of a storyboard. This artifact will help us understand and fashion our story and the major story beats within it.

Nailing down your story beats is huge. I mean that both ways: it is simultaneously really important and it’s a big job. And because it’s both of these, I’m going to need more than a single post to cover it.

In fact, I will write many.

- Constructing a storyboard (this post).

- Completing the Blake Snyder Beat Sheet. I’ll cover this over several posts.

- The beats go on: getting to a full story.

As we go, our storyboard will get more and more complete.

Beats are like Russian nesting dolls

As we’re digging a lot deeper into the idea of story beats, I want to point out something that may or may not be obvious: beats contain beats (contain beats, etc.). Anchor Beats, Key Beats, and other beats may themselves be sections of a story, rather than moments.

Consider, for example, the Finale beat (see my previous post if you need a refresher on the 15 Save the Cat Key Beats), the final push of our protagonist to achieve her goals. A story’s finale may occur in a single scene, but very frequently this happens over several. In fact, Save the Cat has long recognized that a typical finale has five sub-beats (which we’ll discuss in the post on the subject of the Finale). Fun & Games and B-story actually represent nearly all of the first half of Act Two…so obviously there are many sub-beats hidden beneath these two headings.

Even a single scene is composed of numerous sub-beats: “Joe robs the bank” may be a beat. But within that there are many more finely-grained beats:

Joe stands outside the bank, contemplating…can he do this?…thinking of Mary and the kids, he commits; inside, he cases the establishment, just one guard (half-asleep), tellers helping customers, he spots the surveillance camera and belatedly dons his ski mask, draws a toy revolver; strides up to Vita, a gum-chewing teller, who tells him he’ll have to wait his turn, she’s busy helping…she sees the gun, the mask…she gulps, chokes on her gum…Joe’s the only person here who knows the Heimlich maneuver…

I bring this up to specify that for the purposes of this and the upcoming group of posts, what we mean by beats are the coarsely-grained aspects of the story (generally something the size of a single scene or larger).

With that understanding, let’s dive in!

What is a storyboard?

A storyboard is nothing more than a way to observe all the main beats of your story in one place. Digital or real-world, it’s a bulletin board on which you tack index cards representing the (larger) beats of your story.

Why I like a storyboard

The storyboard presents an easy way to understand your entire story and its beats at a glance. Portraying the entire narrative on a physical board (or a digital one, as I do) allows you to play with ideas, reflect on pacing and characterization, and confirm that things are balanced and tight. It shows you where your story is overcrowded or lacking detail, and – depending on how you implement it – can even help you ensure that all your characters and themes get well-represented.

There are lots of ways to go about storyboarding a novel or screenplay, so don’t take this post as any kind of gospel. It simply reflects how I do it and gives you a few ideas you might find useful. If you have other ways of approaching this, let me know about it in the comments.

Figma: my storyboarding tool of choice

I use Figma because it works for me. But tool choice is largely a matter of personal preference, and you may have a different tool that suits you better; I have no intention of swaying you away from something that works for you. Let me simply share why I use Figma:

- Has a free tier (I’m a cheap-ass and I like free stuff)

- Allows me to create plenty of drawings

- Allows me to create plenty of FigJam Boards (this is important, see below)

- Has the minimal toolset I need to create my storyboards

- Because it’s cloud-based, I can take my storyboard with me anywhere and share with collaborators (notice how Figma lets me share both my generic storyboard and my storyboard for Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone below)

Now, to be sure, any web-enabled tool has its drawbacks. Do you really own your content if the data is housed off in the cloud somewhere? Couldn’t someone steal your work? Does the company use my data in some nefarious way? Any of these could potentially be a problem. But for me, I feel like Figma works well and gets me most of the way to a great storyboarding environment. I also have a large monitor at home, so I can display quite a lot on the screen at one time.

Your mileage, as they say, may vary.

Whatever tool you use, let’s get into…

Storyboard: the basics

Let’s look at the skeleton of a storyboard to understand what I’m doing when I build this artifact. What you see below is a FigJam board with an utterly generic storyboard. Zoom in to get a close look. You can even take it fullscreen if you like.

In the FigJam board above, you can see the fundamental aspects of a story as displayed on the storyboard. Let’s call out the major features.

The storyboard has four rows, defining the four acts of any story’s fundamental structure – remembering what I wrote in my last post about the conventional Act Two really being two acts rather than one – one row each for Act One; Act Two, part I; Act Two, part II; and Act III.

Then we set down the Anchor Beats, the five pivotal moments of the plot where the story makes some fundamental shift. I represent these above in red.

Next, we fill in the remaining ten Key Beats as defined by the Save the Cat methodology (or whatever analogous methodology you prefer). I represent these above in orange. We’ll get into the details of these beginning in my next post.

Finally, we fill in all the remaining beats. I represent these in green. Again, I’ll discuss these in a future post.

At its most basic, that’s really all there is to it. Act I beats go in the top row, and so on. The important thing to recognize is that I can, at a glance, see every major beat of my story, including where all my Anchor Beats and Key Beats are located.

Why is this useful?

By setting everything up in this way, I can see my entire story more or less at-a-glance, which events happen where, and ensure that all the elements are balanced as I like.

What goes on a storyboard index card?

This is simple: what happens in the scene. That’s it. Roughly a sentence will do. “Joe robs the bank”. “Harry boards the Hogwarts Express”. “Jack meets Stephen at the Governor’s House”. You don’t need to get detailed at this stage. Neither do you need to describe the significance of the moment as it relates to the characters, the symbolism, or anything else – though see the example below to better understand where this type of information does belong.

Storyboard Example: Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone

In order to make it clear how I construct my storyboard, and to provide a reasonable reference point, I want to include a storyboard breakdown of a book you likely already know. The Harry Potter series has such wide currency that it seems like an obvious choice, so I pulled out my copy and went through it to create an example storyboard.

Spoiler alert, obviously, if you’ve never read the book or seen the movie.

Note that I’ve added one color card on top of the others already listed:

- Red: Anchor Beats

- Orange: Key Beats

- Green: other beats

- Violet: supporting details

These violet cards provide the type of supporting detail I mentioned in the previous section: notes I want to provide myself to ensure that I understand why each beat matters. Putting this info on separate cards instead of, for example, the backs of index cards is a personal choice. I like this approach because I can still easily discriminate scene cards (red, orange, green) from detail (violet), and yet still have all that supporting information readily at hand.

I’m actually going to examine this storyboard a total of three times. In this post, I’ll focus on the Anchor Beats. In the next group of posts, I’ll dig into the Key Beats. We’ll examine the remaining beats in the final post of this group.

Reminder: Anchor Beats

Again, the five Anchor Beats are:

- The Catalyst breaks your hero out of the routine of their life at the beginning of the story.

- Break into Two forces the hero to take an affirmative step to choose adventure. This decision, therefore, drives the events of the first half of Act Two.

- The Midpoint advances the forces of opposition, thus driving the second half of Act Two.

- All is Lost destroys the hero’s new world, so that they doubt their ability to prevail.

- Break into Three forces the hero to find one last thread of hope, so that they make a final push towards success.

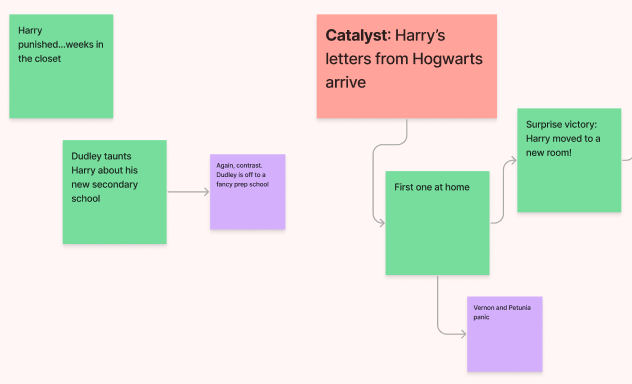

Harry Potter: Catalyst

Harry’s Catalyst is the moment that the first letter from Hogwarts arrives in the post. He’s already been established as a boy of two drastically different worlds: in the muggle world, he’s an orphan living with an abusive family. Little if anything ever goes his way. What Harry doesn’t know is that he’s also a wizard. And not just any wizard but a famous wizard: as a baby he defeated Voldemort, the darkest wizard in history, and impossible expectations await him once he re-enters that world.

The catalyst moment happens about 12% of the way into the book, or a bit less than halfway through Act One.

(A bit of an apology for the video clips. Of course these are from the movie, which in my opinion is a lackluster imitation of a great book; including them is simply intended to jog your memory in case you’re not entirely up on your Potter.)

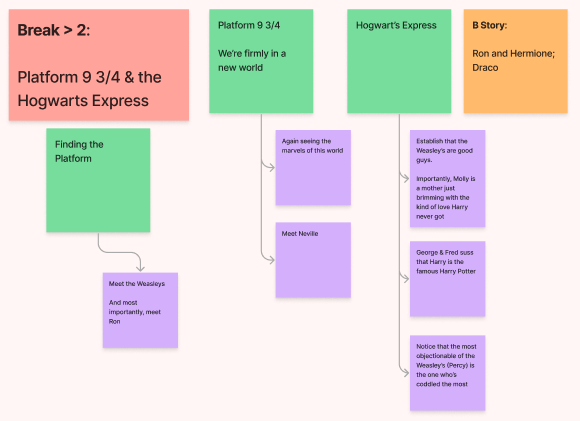

Harry Potter: Break into Two

As soon as he enters Platform Nine and Three-Quarters (29% of the way into the book), Harry is firmly in the wizarding world. He’s certainly dipped his toe in it already – meeting Hagrid and visiting Diagon Alley – but this is his Break into Two moment, truly the point of no return: any doubt or uncertainty, any interference from his abusive relatives, that’s over. And immediately Harry is spotted for who he is…not just another student, but the famous Harry Potter. This Theme, stated for the first time by Dumbledore in the first chapter (“famous before he can walk and talk!”), is core to Harry’s journey in this novel.

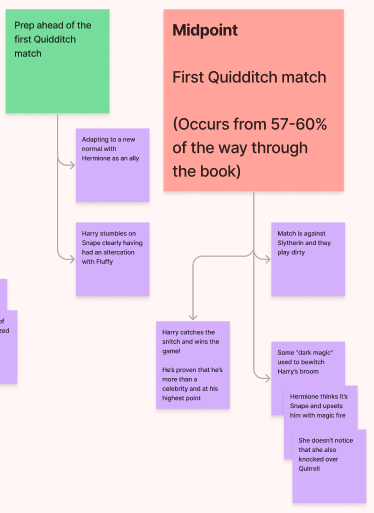

Harry Potter: Midpoint

Harry has a generally upward trajectory through Act Two, part I. He meets Ron and Hermione (his allies who establish the main B-story), and overcomes various obstacles (run-ins with the nasty Draco Malfoy, a harrowing Sorting, a vicious Potions master, trolls, baffling magic, strange creatures, etc). Through it all, he is dogged by his celebrity. Other students and professors variously scold, mock, or revere him for it. Can he become more than his reputation?

Harry’s Midpoint occurs at his first Quidditch match, occurring 57%-60% through the book. He’s at his peak here – what we call a “false victory” – succeeding in the match and demonstrating that he’s more than just a famous name. But in the same moment we see stirrings of Bad Guys Close In: some ally of Voldemort is using dark magic to try to kill him!

This “midpoint” – coming about 60% of the way into the story – may seem a bit late from a purely mathematical point-of-view. But in the context of a story with considerable world building, I’d say this is within a reasonable tolerance.

In fact, I’ve often found my own midpoints often arrive a bit “late“. I attribute this both to time spent on world/character building, and on the inherent nature of pacing, which often increases in the back half of Act Two.

And indeed, J.K. Rowling picks up the pace after this Quidditch match: in quick succession Harry faces a number of new challenges. Who is Nicholas Flamel? What’s Voldemort looking for? What is the secret of The Mirror of Erised? Is Hagrid hiding something in his hut? What’s lurking in the Forbidden Forest?

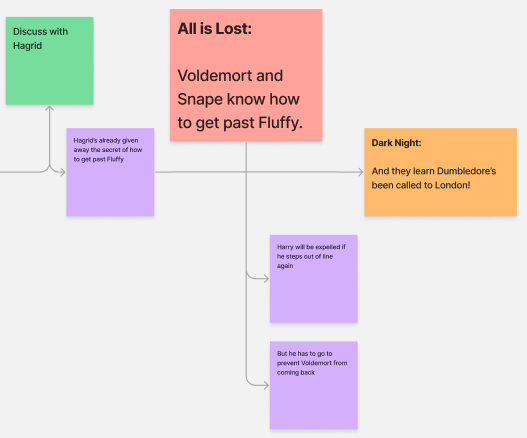

Harry Potter: All is Lost

As Harry and his friends wrap up their final exams, the real test has been the unraveling of the mystery of Voldemort’s quest. They’ve already learned that he’s after the Philosopher’s/Sorcerer’s Stone, but everything comes to a head 80% of the way through the book as Harry realizes that Hagrid has accidentally given Voldemort (and, he believes, Snape) all the information necessary to get past Dumbledore’s protections. Worse, Dumbledore himself has been lured away from Hogwarts. All is Lost!

Harry’s celebrity won’t help him now. Unless he really is more than just some famous kid who got lucky as a baby, he’s going to get himself and his friends killed trying to save the day.

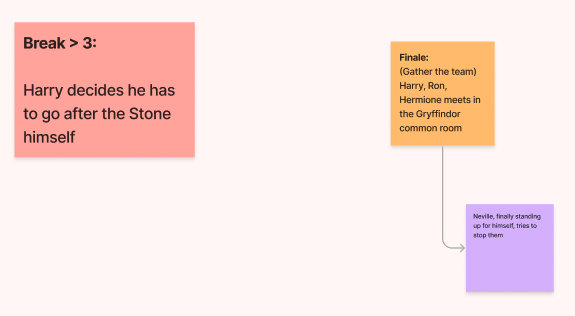

Harry Potter: Break into Three

It must be said, Rowling doesn’t spend a lot of time on All is Lost or on Harry’s Dark Night of the Soul. All of this happens in just a few pages before Harry Breaks into Three by deciding that he needs to get to the Stone before Voldemort does.

This takes us straight into the Finale and a series of hair-raising vignettes that culminate in Harry’s final confrontation (for now) with the dark wizard from his past.

If you look back at the storyboard above, you can easily pick out all five of these critical moments, get a sense as to where they fit and what other elements surround them.

As I’ve explained, we’ll dig ever more deeply into this storyboard over the next couple of posts.

Storyboarding bells & whistles

A couple final ideas for your continuing storyboarding adventures…

One thing storyboards are really good for is giving you a sense of perspective and balance. I’ve also found this tool invaluable for adding depth and texture to my story.

Special feature: storyboard swim lanes

To assist with balance, I will sometimes add extra dimensions of detail to my storyboards. For example, my current story has four key “swim lanes” to the story: scientific discovery, politics, personal growth, and action/adventure. I’ve arranged swim lanes – horizontal bars within the acts to indicate each of these four areas of storytelling.

By placing each beat into the swim lane that the beat deals with, I can easily see which of my areas get adequate attention and which are lacking. To be sure, sometimes a beat belongs to more than one lane, but the tool nevertheless works as a rough guide for rebalancing elements.

In an early draft, seeing the distribution quickly revealed that the action/adventure element in my story wasn’t strongly represented enough in Act Two, enabling me to rethink and strengthen that element.

Another potential way to use this feature might be to establish swim lanes based on characters, ensuring no main character gets “forgotten” for too long.

Special feature: different storyboards for each main character

I believe that everyone is on their own journey. Obviously your main character is. But so are other characters. And the journey they’re on may be different from the one that the hero is on.

Take Neville Longbottom from Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. While Harry gets all the glory for being The Boy Who Lived and winning at Quidditch and defeating Voldemort (again), Neville is on a far more intimate – and honestly far more relatable – journey as he deals with insecurity, self-doubt, bullies, and an overbearing grandmother. In his small way, Neville is on just as big a journey as Harry, something which becomes far more apparent by the final novel in the series. Note that Rowling makes a key editorial decision: it is Neville’s ten points – rather than Harry, Ron, and Hermione’s collective 160 – the decides who wins the House Cup. And Harry’s joy in the collective victory over Slytherin is the antithesis of what concerned Dumbledore at the start: Neville helps Harry become focused on what’s good, rather than what’s good for himself.

I’ve found that mapping out the story from the perspective of other major characters can greatly improve their dimensionality. As I see the story from their point-of-view, I literally discover who they are. I find more interesting motivations for how they act and why, almost always enriching the story.

Consider this also: the Anchor Beats for your hero might not be the same as the Anchor Beats for another character. I have no idea what Neville’s Catalyst moment might have been, but it certainly had a different flavor than Harry’s. His Midpoint, I suspect, is when he tells Malfoy “I’m worth twelve of you”. It’s a seminal victory for him to be able to stand up to anybody, even though he gets laughed at for making the attempt.

These other stories orbit your main story, but they are different tales. They might begin a long time before your story begins or even continue well after it ends.

Storyboard on!

In the next post, we’ll begin to dive into the rest of the Save the Cat Key Beats and again investigate how those beats are represented in Harry Potter.

Plotter-Oriented writing is how I avoid some of the biggest pitfalls of writing a long-form work like a novel. If this interests you, please let me know what you think in the comments, and consider subscribing to my blog.

Leave a Reply