NPS – net promoter score – is a tool used by marketers, product managers, and business strategists to assess customer loyalty, satisfaction, and enthusiasm.

I’m going to start with a one-two punch of why you shouldn’t read this article.

First, if you want to write a book, write the book. Enjoy it! Have fun! User reviews should be the least of your worries.

Second, I might not know what I’m talking about. My experience is as a product manager and an engineer. As I sometimes do in my posts, I’m applying my business experience to the world of book-writing, and what follows makes sense to me. But those who know this specific business better might tell me that the approach I’m suggesting is wrong-headed. If so, I’d love to hear their thoughts in the comments.

Those qualifications out of the way, here’s why I wrote this. I recently saw someone on Threads fretting over what to make of the 3-star reviews they were getting on GoodReads. My answer is to provide a framework based on a tool I use in my other life as a product manager.

If we’re going to fret over our book’s reader reviews (and I fully expect I will do this when the time comes, just the same as any writer!) we might as well do so using the same model used by most businesses to assess customer enthusiasm. By giving us a bit of context, this can turn a pointless hand-wringing exercise into something that actually helps us act on the information.

If you’re trying to assess whether a problem relates to product quality (is my book any good?) or marketing (is it finding an audience?), an NPS examination is a good place to start.

What is a net promoter score?

NPS, or net promoter score, is a calculation which businesses use to assess and compare the enthusiasm of their customers. It looks at a very narrow data set to gather a blunt user assessment that can be compared with others.

It’s largely analogous to the five-star review system commonly used on book review sites like Amazon and GoodReads. Adapting star reviews to NPS can help an author understand how their audience feels about their books, and to benchmark themselves against “what good looks like”.

Remember as we go that a promoter score is usually based on a pretty large data set. So don’t sweat over any single review (or even a group of them). Even The Great Gatsby, To Kill a Mockingbird, and Hamlet get one-star user reviews.

NPS is built on a single, simple question:

On a scale from 0-10 how likely are you to recommend this [thing] to a friend or colleague?

Breaking down the definition

The “thing” in question may be a company, a product, a service, or even a book. Let’s dissect this definition to understand why it might be useful to authors trying to decode the reviews they see of their books.

First, the 0-10 scale creates a standard. Since everyone across industries tends to ask this same question on this same scale, one can establish a certain consistency (but don’t think it’s perfect…it’s just a number). I can look up other businesses in my industry to see how I stack up against the best and worst. If I know Netflix has an NPS of 68, Airbnb 74, and Tesla 96, then I have some idea what “good” looks like in these industries. And the more comparable data I get, the better I can rate where my company (or product or book, etc.) stands.

Second, the question asks not “how happy are you?” but “how likely are you to recommend this [thing]?” That’s interesting, isn’t it? NPS is driving not at satisfaction in itself, but at virality. In other words, would you tell someone about it? A satisfied customer is great, but what we really want are customers so satisfied they’ll market on your behalf.

Finally, note that we’re asking “how likely are you to recommend this [thing] to a friend or colleague?” On the reasonable supposition that the average person has friends who share their interests and colleagues with similar professional needs, this suggests that the respondent who likes the [thing] will help create buzz among a like-minded audience. And that makes intuitive sense: in my personal life, I gravitate towards folks who like the things I like. In my professional sphere, I often recommend tools that help me do my job (as I’m doing with you right now).

Scoring based on the traditional NPS scale

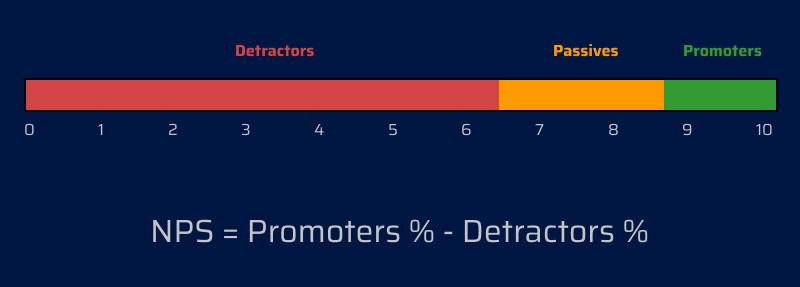

So how do we apply this score? Steel yourself, ‘cause it ain’t pretty. Here’s how the calculation is most commonly used:

Only the 9s and 10s are considered “promoters”. These are the folks who really love what you do, and you should expect them to want to tell everybody how amazing you are.

The 7s and 8s are pretty happy. They like you and they might even purchase from you again. They’re pretty happy but they’re not very happy. We call these “passives” and we throw everyone who gives us this level of approval away. (I warned you, it ain’t pretty).

This leaves everyone 6 and below as “detractors”. These are the folks who are at best “meh” on what they got, and might even be your sworn enemies. At best, you can hope they’ll keep their big mouths shut. At worst, they’ll utter words you wouldn’t like your mom to hear.

The calculation to get an NPS is therefore:

NPS = % promoters – % detractors

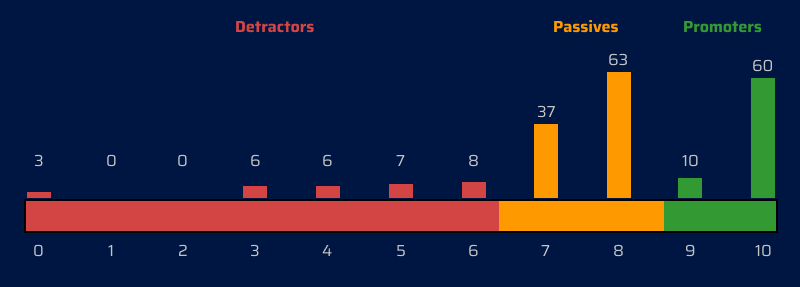

Example: if I have 200 reviews like so:

At a glance, this looks really good. My reviews are clustered to the right so I probably feel pretty happy. But notice how much of the graph is clustered among the “passives”.

- 70 people (35%) gave me 9s and 10s (promoters)

- 100 people (50%) gave me 7s and 8s (passives)

- 30 people (15%) gave me 0s through 6s (detractors)

NPS = 35% – 15% = 20

My net promoter score is 20.

Is that good? That depends. For some industries or products, a score of 20 would be above average. For others, that would be disastrous. The 96 I mentioned above for Tesla, for example, is extraordinary by any measure. Compare that to where Qualtrics puts the average company in the auto industry (2021): a mere 14. Netflix’s 68 puts it well ahead of its competition: Qualtrics puts streamers (2021) at an average NPS of 28.

Converting NPS to star ratings

I think that the star rating systems on GoodReads and Amazon are a pretty decent proxy for the NPS question. After all, when you leave a review on one of these sites, you might be thinking “am I happy?” But by posting a review, what you’re essentially doing is saying to a person considering the book (a like-minded individual) whether or not you recommend it.

Online review systems are, of course, subject to weird quirks, such as review bombing and herd mentality, so always take this – and indeed any single measurement – with a grain of salt.

So how shall we convert the NPS question to star ratings? I’m going to recommend the most obvious, cold-blooded approach:

- 5 stars = promoter

- 4 stars = passive

- 1-3 stars = detractor

You might be thinking “but those four star reviews are good aren’t they?” I respond “yes, they are. And you should be proud of each and every one you receive.” But that’s not the question we’re asking. We’re not asking “is it good?” but rather “is it leading to enthusiastic virality?” We want to compare our best promoters with our detractors, and the 4-star reviews are people who liked what we did…but maybe they didn’t quite love it. And they certainly can’t be relied on to tell their friends “you must read this book!”

So let’s go back to my example above where my calculated score was 20. Had I included my 4s, my passives, I’d be very happy indeed. But I’m being harsh with myself the same way I imagine my publisher (or anyone else with a vested financial interest) would be.

Is 20 good? Having seen examples from a few industries you can guess that the answer is “probably not”. But that’s not certain yet.

The data: what good looks like

What we need to do is to look at comparables in order to make sense of the data. If we’re writing in a genre, for example, it would be helpful to look at similar titles to discover what success means. Fortunately, both Amazon and GoodReads provide tools to make this relatively straightforward. Let’s look at a recent darling of the fantasy (and BookTok) world: Rebecca Yaros’ Fourth Wing.

If you follow the links, you’ll see that both services conveniently give you not just a review average, but a star breakdown that makes calculation easy.

As of the moment I’m looking, here’s the data I see (numbers may be rounded in some cases):

| Rating | Review count | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amazon | 5 star (promoters) | 141,579 | 86% |

| 4 star (passives) | 18,108 | 11% | |

| 1-3 star (detractor) | 4,939 | 3% | |

| Total | 164,627 | 100% | |

| GoodReads | 5 star (promoters) | 894,183 | 72.3% |

| 4 star (passives) | 241,665 | 19.5% | |

| 1-3 star (detractor) | 100,590 | 8.1% | |

| Total | 1,236,438 | 100% | |

| Combined | 5 star (promoters) | 1,035,762 | 73.9% |

| 4 star (passives) | 232,773 | 16.6% | |

| 1-3 star (detractor) | 105,529 | 7.5% | |

| Total | 1,401,065 | 100% |

Giving us (remember NPS = % promoters – % detractors):

- Amazon NPS: 86 – 3 = 83

- GoodReads NPS: 72.3 – 8.1 = 64.2

- Combined NPS: 73.0 – 7.5 = 65.5

Congratulations Ms. Yarros! This is probably an excellent example of “what good looks like”. (For reference, A Game of Thrones scores a combined 49.1.)

If your fantasy novel gets this NPS, the question to ask yourself almost certainly isn’t “how do I write better books?” (Though of course we all strive to be better.) A more important question would be “how can I get this in front of more readers?” because when readers find it, they like it! On the other hand, if your numbers are lower, that suggests that there’s something that isn’t quite hitting home even when a reader finds you.

You can base your comparison off of Amazon, GoodReads, or both, but I’d generally suggest getting the broadest sample size possible, especially as most of us don’t garner 1.5 million reviews.

The data: what “pretty good” looks like

Ideally, the next piece of data we’d like to see is some kind of average. Comparing ourselves to a runaway hit might depress us if we’re not quite so beloved. Having a “genre average” would be helpful because we could use the two numbers as lighthouses: it’d be great to know where we stand relative both to “good” and “meh”.

Unfortunately, this is harder information to come by. GoodReads no longer supports its API, making it difficult to scrape this kind of data. Someone could probably build this tool for Amazon, but as you may have noticed, the data pool for Fourth Wing on Amazon was a lot smaller than on GoodReads (and curiously a lot more positive…maybe someone more familiar with the community on GoodReads can explain that to me in the comments).

Lacking this type of data doesn’t mean that we’ve wasted our time. Far from it. I’m simply pointing out that it’d be a lot better to have more data points to reference. My suggestion for you, therefore, is to grab a number of books in your genre and do the calculation by hand. It’s not hard, even if it is a little time consuming – but we writers all love a bit of procrastination, amiright?! Ten or so of these, grabbed at random from your comparables, will give you some numbers to shoot for and some idea where you stand relative to others.

Hopefully that covers everything. Again, I’d much rather you just write out of sheer joy, but a bit of added business understanding can help turn our worries about reader reviews into something genuinely useful.

If you have thoughts or questions, please post them in the comments. And as always, I’d appreciate if you’d join my subscriber’s list.

Leave a Reply