So here’s a question: you’re writing a fantasy or science fiction story. You almost certainly have to invent new words for magical powers, alien beings, new technologies, and curious locales. How do you go about inventing words that make your world feel coherent and believable? I employ the powers of etymology.

How do you approach this problem in your stories? Tell me about it in the comments.

Imagine words divorced from their history.

The truth is most people do this without imagining; it’s the straightforward business of everyday communication. If I go into a restaurant and order “a burger with fries, hold the ketchup, extra mustard and mayo for the fries” it’s doubtful that I’m pondering my meal’s relationship to a panoply of exotic origins: Germany (maybe), France (not at all), China, Italy via France, and the outcome of a particularly thrilling naval action just off Minorca.

But when you get down to the exacting business of writing, where every word seeks to drive a point with rapier precision, history becomes inescapable. “Fatal” does not merely mean deadly; it carries the weight of “fate” and “the three Fates”, potentially implying the intercession of divine forces. “Romantic” is more than roses, starry skies, and wooing lovers; it’s a history of idealistic poets and painters, building on chivalric tales which themselves hearken back to Roman times.

Real housewords of well, everywhere

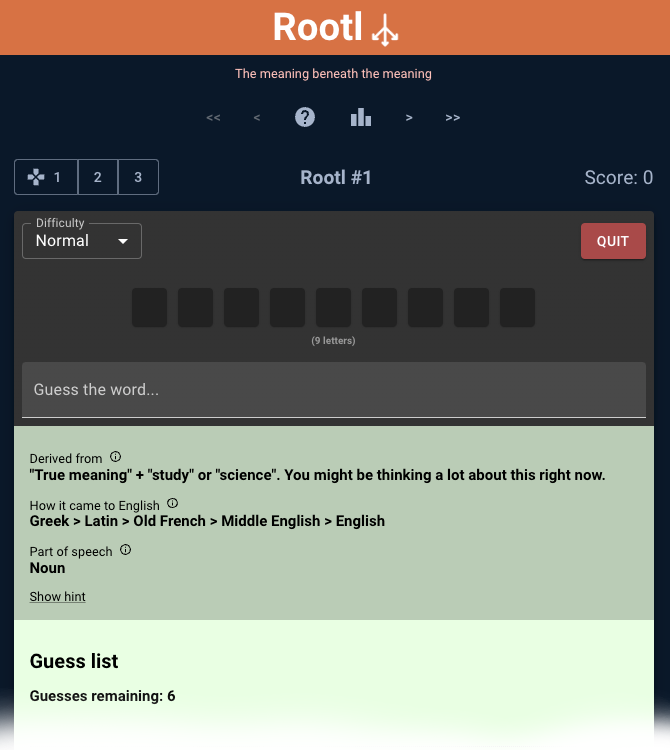

This topic has troubled me of late. You see, in addition to writing, I run a daily word game called Rootl which focuses on etymology – the history of words. So I think a lot…more than most people, I suppose…about where words come from.

And when you think about where words come from, and you happen to be writing a novel that takes place in a fantasy world, you begin to run into a peculiar conundrum. The inhabitants of my otherworldly realm choose their words using the day-to-day tools of language: a confused mishmash of logic, tradition, folk custom, slang, vowel and consonant shifts, scriveners’ errors, uptight grammarianism, loan words, cognates, and neologisms. But my audience and I share a peculiar limitation in this regard: neither of us knows how to communicate using those words. The words of a fantasy world.

The words we know how to use are from a different dictionary altogether: English.

In some ways, our world is no different.

The whacky etymology of English

English is a rich language for precisely the same reasons that make it devilishly hard to learn. While some languages – I’m looking at you, French! – have attempted to maintain control over their lexicon, and others simply never reached such an immense scale, the expansion of English across so much of the globe led to the spectacular failure of its word police. And we have been the richer for it.

The vast majority of Modern English stems from French and Latin roots (while the core of our language is Germanic, only a rough quarter of our words derive from that source). The grammarians of the 19th century attempted, like the French, to put neat white picket fences around the primroses of our speech, no doubt thinking they were enforcing a sort of “purity” of expression. Thus one couldn’t split an infinitive (because one couldn’t do this in Latin!). A sentence never ended with a preposition. And make sure you know where you stand on “color/colour” and “theater/theatre”. New words – as they still are in French as enforced through the Académie Française – were largely frowned upon if not forbidden outright.

But as English spilled into the Americas, into India, Oceania, Africa, the South Pacific, and elsewhere, it simply outgrew all efforts at lawn-tending. Possibly the American affection for democracy played a role: the PEOPLE, by God, will decide what is acceptable! But however it happened, the English language slipped away from the groundskeepers’ control, allowing the language to build ceaselessly on those Germanic and Franco-Latin roots.

Modern English increasingly borrows, invents, and reshapes words to its liking, so much so that many of us look forward to the “Word of the Year” with more anticipation than Time’s “Person of the Year.” For my part, I know the former (only recently learning the latter was Taylor Swift): Merriam-Webster went with “authentic”.

Oxford chose “rizz”.

And rizz is, in fact, an excellent example of English’s delightful and disgusting slipperiness. It derives from “charisma”, but by pulling out the middle of the word, its coiners twisted it almost beyond recognition, establishing a term with its own unique shading. It’s a word that would doubtless cause Samuel Johnson, Daniel Webster, and Herbert Coleridge to form a lexicographer’s brute squad. But there’s nothing you or I can do to stop it. The PEOPLE, by God, will decide.

Fantasy etymology

So let’s get back to my fantasy world, a world full of parallels to Earth, but perhaps not Earth; a world that feels recognizable, human, ordinary even, apart from the fact that people in my world live in an island archipelago where the “islands” are mountaintops, and the “sea” is a layer of poisonous clouds. My denizens have, in their clever way, invented airships which sail above this cloud sea much as adventurers in our Age of Discovery plied the waterways of Earth.

Which brings me to the words we choose when spinning a fantasy yarn.

It’s a delicate business inventing language. You want to create a rich, inviting, textured world, but you don’t want to confuse or alienate your audience. The further your world strays from the conventions of the familiar, the more profoundly they must leap to stay with you.

There’s an old notion in comedy…a joke is funnier if the audience successfully makes a leap. This same might idea be true in world building.

There’s an old notion in comedy that probably applies here: a joke is funnier if the audience successfully makes a leap. If there’s no leap – the joke is too obvious – it’s not funny. If the audience fails to make the leap – they don’t get it – it’s not funny. The funniest jokes require the furthest successful leap…so the audience isn’t simply laughing at the joke, they’re secretly, unconsciously proud of themselves for crossing the chasm with you.

I suspect that world building works in much the same way. Too simple and the world isn’t sufficiently interesting. Readers of science fiction and fantasy want to be taken to faraway, inventive places. And interesting language is part of the texture of that invention. Too complicated and your audience will start to wonder what the fizzbin that Benzite GhojmoK put in the raktajino. It’s our job as writers to strike the right balance. Perhaps the best worlds are deep and rich, but so cunningly crafted as to conscientiously educate the reader along the way, so that they just “get it” rather than constantly refer to a glossary.

(Side note: if you’ve never seen Tom Stoppard’s Dogg’s Hamlet, check it out as an awesome example of language building. While the actors perform the majority of the play in nonsense-words, Stoppard’s careful crafting leads the audience to understand the nonsense by the end.)

The etymology of deep-space teddy bears

Here’s an example of good and bad “wor(l)d building”, using teddy bears and two popular science fiction franchises.

In Star Trek, Dr. McCoy once made fun of Spock upon hearing that as a child the emotionless Vulcan officer had a teddy bear. Spock quickly clarified that his teddy bear was “alive…with six-inch fangs.”

Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (in the novelization) also referred to the Ewoks – the stout yeomen defenders of Endor – as “teddy bears”. The term quickly described the bear-like creatures, but it felt like lazy writing.

The former example makes sense: Star Trek takes place in our own future. While McCoy may or may not remember Teddy Roosevelt (or understand the etymological connection), the idea of a teddy bear in his list of available terms is – to quote Spock – “logical.” But even as a child the usage in Star Wars felt ungainly: how could anyone “a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away” even think of comparing the Ewoks to a stuffed Earth animal once presented to the president of an Earth nation?

Sea language for airships

What feels glaringly true for the teddy bear is only slightly less irksome for me in terms relevant to my story. My airships, for example, need to turn right and left. What terms should I use for this?

The naval standards are “starboard” and “port”. These terms didn’t appear wholly formed when Odysseus – receiving a vision by the grace of Athena – awoke one morning and started using them. They extend, rather, from a rich historic tradition: early German sailors propelled and steered their boats using a paddle on the righthand side. Old English steorbord, literally “the steering board” referred to the “board”, or ship side, on which the steering was done. Because this steering paddle occupied the righthand side, sailors reserved the lefthand side for “lading” or loading the ship. Thus, the opposite of starboard was “larboard”, or ladde-borde in Middle English: the ship’s loading “board”.

Of course only one of these terms survives in common usage. The two terms simply sound too much alike. In a raging storm, rocks off the bows, with all lives on the line and a precious cargo in the hold, no one wants to mistake a turn to starboard for a turn to larboard. Thus some centuries later sailors exchanged the word “larboard” for “port”. The new term was far less subject to confusion, and meant essentially the same thing; even though steering paddles had long since fallen out of usage, the tradition of docking ships on the larboard side had persisted. Thus a ship’s “loading side” was also its “port side”, the side which faced the port.

OK, so let’s dispense with all this turbulent history for now. As I mentioned, we probably don’t want to overload the reader with new terminology when our own language has perfectly acceptable terms to meet the moment. Invention should deepen the world, not muddle it needlessly.

But these are airships – they go up and down – so there’s a third dimension to consider.

Maritime terminology only accounts for the first four of these.

Obviously, a sailing vessel’s vertical motion extends only to the limits of the rising and falling of the waves. Any greater motion in that axis is called “sinking”. There are certainly terms for rotation (yaw, pitch, roll) and translation (sway, surge, heave), but a lack of practical necessity means that sailors have no nautical equivalent to starboard/port/fore/aft in reference to verticality.

I had hoped to solve this problem by consulting airplane and helicopter terminology. But these are far newer technologies – and hazardous conditions aboard these vehicles mature very quickly! – thus their language emphasizes ruthlessly efficient radio traffic. Directions tend towards absolutes (“turn to two-niner-five, ten thousand feet”), and prosaic words like “right” and “left” replace words steeped in tradition. Suffice it to say that such dried-out language – while sensible when real lives are on the line – sits uncomfortably alongside the eccentric esoterica in which a mariner’s language is steeped.

I need to build on linguistic history so that real and invented terms harmonize. Simultaneously, I must ignore the very historical tapestry that created the real terms in the first place.

So not only will I need to accept words necessarily disconnected from their linguistic history, I will also need to invent new words to cover areas which do two contradictory things. First, build on that linguistic history so that real and invented terms harmonize. Simultaneously, I must ignore the very historical tapestry that created the real terms in the first place.

Tolkein’s etymology

Tolkien, that erudite philosopher, linguist, and historian masquerading as the greatest fantasy author of all time, understood this problem acutely. He had a reputation for inventing new languages over breakfast, based on his vast understanding of ancient Germanic tongues. Thus he never seemed at a loss for Elvish, Dwarvish, or Orcish words (never forgetting that each of these came in a selection of dialects) to suit a given situation. One would never catch one of his hobbits within a mile of a teddy bear, however well that might play in hobbit slash circles.

Tolkien applied words powerfully precisely because he understood etymology and bent it to his will. The word mithril, for example, an almost magical metal, has its own etymology. And not an English etymology, nor even a Norse etymology, but an Elvish etymology: mith meaning “grey” + ril meaning “brilliance”. And just to prove this is no random construction, the root mith in mithril is the same as the root of Gandalf the Grey’s Elvish name Mithrandir, a name that translates as “grey pilgrim”.

Example etymology from my world

Not being as gifted a linguist as Tolkien, I’ve had to rely on my comparatively feeble understanding of Old English, French, and Latin. For example, in a bit of lore building for my world, where I discuss the history of flight, I reference a distilled liquor called sureau. I invented this word to serve my purpose – distillation being a key technology in my world’s history – and it combines several threads of thought.

First, I mash up a bit of Old English (sur “sour”) and French (eau “water”). In a literal way, “sour water” simply describes the nature of the drink. As in English, my modern words tend towards the French while my more classical terms favor English’s Germanic heritage. So this looks like a transitional word.

Second, I borrow from the etymological origins of whisky (yes, I like whisky). Gaelic uisge beatha, meaning “water of life,” is a much-borrowed term as seen in a variety of spirits such as aquavit, eau-de-vie, aqua vitae, and possibly even vodka. My nod here is subtle, simply paying homage if you will to another “spiritual” tradition.

Third, another important term in my world is the sursum, the poison cloud layer forming the “oceans” of my world. Sursum itself comes from a Latin word meaning “up”; directionality, as you can see, is core to the fabric of my world. To make sureau, distillers in my world sour their wine by exposing it to the poisonous gasses of the sursum prior to distillation. Thus, sureau has not only a true etymology, but additional complications that make its history challenging to pick apart (a common feature in real words).

Finally, the word “sureau” has an actual French meaning: elderflower. This suits me along several dimensions, including the fact that raw elderberries are poisonous; that (when processed) they have a pleasing flavor; that the plant suggests something “elder” or “ancient”; and that all of this may at some remote or immediate level feel like a real word to the reader.

Does it all matter?

To be clear, such questions as finding words that mean “up” and “down” – or the right name for a shot of booze – are just the merest hair on a dimple on the chin of the face of my novel. Such a detail as to make you cry – and perhaps you’ve done so already – “just get on with it and write a good story, you navel-gazing ass!”

And at some level you’d be right (or…starboard?). The deepest duty of a writer, whatever else they have to say, whatever pearls of wisdom they have to impart, or thrill ride they wish to take us on, is to tell a tale so gripping that you have to read it. Only then will all the rest shine out.

But I submit that a great story with a great hero is the bare minimum of what we owe our readers. The table stakes. The real trick is immersing your reader in a complete world, whether that’s a galaxy far, far away, a hobbit’s hole in the ground, a crime scene in mid-Manhattan, or an airship sailing over a poisoned sea. The language we use – while no substitute for a great story – constitutes the greater mass of chips we have to play in service of that goal. Creating a fantasy lexicon, therefore, enriches the pot. By adding neither too many new terms nor too few, by leading the reader to understand their proper use, and by modeling them based on a believable set of rules, a writer creates depth in much the same way she does by properly understanding her world’s back story.

So “up” and “down”?

“Keelboard” and “mastward”?

“Alow” and “aloft”…?

I think I need a glass of uisge beatha.

Leave a Reply